Knowledge Centre

Jersey's Political System

Introduction

Jersey is a British Crown Dependency, fully responsible for its own internal affairs and with considerable responsibility for its external relations. It is a parliamentary democracy with a single chamber Parliament called the States Assembly. Jersey's government is led by the Council of Ministers, who are selected from and by the Assembly. This paper explains Jersey’s political system and puts it in the context of political systems generally.

Summary

National parliaments tend to be unicameral (single chamber) or bicameral (two chambers). Elections can be by a “first past the post” system, an alternative vote system, proportional representation, or any combination of the three. In some countries, the USA and France for example, the political head is elected directly by the people, while in others, the UK and Germany for example, the political head is the leader of the party that can command the most support in the parliament.

Jersey has a unicameral parliament, the States Assembly, elected every four years, and a government, elected by the Assembly. Both the legislation and custom and practice refer to the “States of Jersey”. This expression is used at various times to describe the government, the parliament, and the Island. For the purposes of understanding the internal political system it is easier to refer simply to the government and to the States Assembly.

Jersey does not have a traditional party system, but this is a matter of practice, not of law, and political parties are present in Jersey politics.

The States Assembly currently comprises the constables (or 'Connétables') of each of the Island’s 12 parishes and 37 deputies elected in nine multi-member constituencies based on the parishes.

Prior to the 2022 election, there were 12 constables, eight senators elected on an Island-wide basis, and 29 deputies in 14 constituencies. The changes for the 2022 election meant that there was much less geographical variation in the ratio of population to elected representatives.

General elections are held every four years. With effect from the election being held on 7 June 2026, the Assembly will comprise the 12 constables, nine senators elected on an island-wide basis, and 28 deputies.

The States Assembly has five standing scrutiny panels, a Public Accounts Committee, a Planning Committee and a Privileges and Procedures Committee. The President of the Scrutiny Liaison Panel holds the most important non-Ministerial political role in the Assembly.

Jersey's government is the Council of Ministers. It comprises the Chief Minister and at least seven other Ministers, all of whom must be members of the Assembly. The Chief Minister nominates Ministers, but the Assembly has the power to elect alternative candidates. Ministers are able to appoint Assistant Ministers, but the number of Ministers and Assistant Ministers cannot exceed 21.

As a feature of Jersey’s unique system, the 12 parishes play a particularly important role in Jersey’s political system, at the parish level and through direct representation in the States Assembly.

Legislation is made in a similar way to other jurisdictions, with the proposition for a new law being presented to the States Assembly. The draft law goes through a number of stages before being finalised, following which it is submitted to the British Privy Council for formal approval and then registration by the Royal Court.

The nature of Jersey’s political system and the weakness of political parties mean that in practice the States Assembly and individual members of it are in a relatively strong position in relation to the government. In particular, Ministers are not bound by collective responsibility, and the standing orders of the Assembly allow any member to bring forward a proposition for a policy or law which then has to be considered.

Types of political system

Democratic political systems typically have two basic features - an elected parliament and a government - but there are significant variations in how the parliament is constituted and elected, as well as how governments are formed.

A key feature is whether there is a single chamber (unicameral) parliament or a two chamber (bicameral) parliament. Out of 190 parliaments in the world, 111 are unicameral and 79 are bicameral. Where there are two chambers, the “lower” chamber is generally elected by popular vote and the “upper” chamber by one or more of either popular vote, appointment, or patronage. For example –

- The United Kingdom has the House of Commons elected by constituencies broadly based on the number of electors, and the House of Lords, most of whose members are appointed by the government. The House of Lords includes representatives from different political parties, independent members, hereditary peers and Bishops. As the House of Lords is unelected and the governing party does not have a majority of its members, it uses its powers sparingly, recognising the supremacy of the Commons.

- The USA has the House of Representatives, elected by constituencies based on population, and a Senate with two representatives of each state, from the smallest to the largest. The two houses have equal, though are not identical, power - the House controls revenue bills, whereas the Senate confirms treaties and senior appointments along with conducting impeachment trials.

- Australia has a House of Representatives, elected by constituencies based on the number of electors, and a Senate with representatives from each of the States and territories.

- France has a National Assembly, elected by constituencies based on population, and a Senate, the members being chosen by an electoral college of local elected officials.

Denmark, Sweden, and New Zealand are among the countries with unicameral parliaments.

It will be noted that some countries use population numbers to determine constituencies while others use electors.

A second feature is the type of electoral system –

- The “first past the post” system (FPTP) simply means that the candidate or candidates who receive the most votes win. Take, for example, this election result for a single member constituency –

- Candidate A 25,000

- Candidate B 21,000

- Candidate C 20,000

- Candidate D 18,000

- Candidate E 14,000

- Candidate F 2,000

-

- Candidate A would win, although with just 25% of the votes. If this was a two-member constituency, then candidates A and B would be elected. The large number of “wasted” votes is widely seen as a weakness of the FPTP system. It encourages tactical voting, where electors vote for a less-preferred candidate rather than their ideal choice because that candidate has a greater chance of winning and can prevent a more disliked candidate from being elected.

- The “alternative vote” system aims to rectify this shortcoming of the FPTP system. Electors rank candidates in order of preference, so as to seek to eliminate the large number of “wasted” votes on candidates who do not win. The first preference votes of the candidate who has fewest votes are reallocated to the second preference of those voters. The process continues until one candidate has more than 50% of the votes. So, in the above example, Candidate F’s votes would be reallocated to the second preference of the voters and so on. The result could be a win for any of the other candidates. A variation, used in France for example, is for an election to have two rounds. If no candidate has 50% of the votes in the first election, then the two candidates with the most votes have a run off.

- The “proportional representation” system seeks to ensure that the composition of the parliament reflects the share of the votes taken by each party and therefore can work only in a party-based system. Proportional representation works though large multimember constituencies. For example –

- Conservative 500,000

- Labour 300,000

- Liberal democrat 200,000

- Green 100,000

-

- If there were ten seats, Conservatives would have five (50%), Labour three (30%), Liberal Democrats two, (20%) and Green one (10%). With this system, people cast their vote for parties, not candidates. Parties have to rank their candidates so the first on their list is very likely to be elected and the last almost certain not to be. However, some systems allow votes to express support for individual candidates as well as parties.

An alternative form of proportional representation is electing single members in constituencies but then using a “topping up system” to reward the parties whose share of the total vote exceeds its share of elected members. The Scottish Parliament uses this system.

In the same way as there are different ways that a parliament can be constituted, there are different ways in which a government is formed and the consequent relationship between that government and the parliament. There are two basic models –

- A presidential system in which the head of government is also the head of state and is elected directly by the people. This can be through a simple majority of votes cast, as is the case in France, or it can be based on an electoral college where it is possible that the winning candidate does not have a majority of the votes. The latter is the case in the USA, where the electoral college depends on the results of elections in each state. With this system, the president appoints ministers who generally are not also members of the parliament, thus effecting a distinct separation between the legislature (the parliament) and the executive (the government).

- A parliamentary system in which the leader of the party in the parliament that commands a majority becomes the prime minister, and where most, if not all, of the ministers are also members of the parliament. This is the case in the UK. However, it is not necessarily the case that the party that can command a majority is the largest party. In a system where multiple parties have seats, the issue is which combination of parties can be secured. In these cases, it may be the third or fourth largest party that determines who will form the government. For example, in the 2010 British election, it was the third largest party, the Liberal Democrats, that determined that there would be a Conservative-led coalition rather than a Labour-led coalition.

Jersey’s system in context

Jersey has a parliament in the form of the States Assembly and a government, but both the legislation and custom and practice refer to the “States of Jersey”. This is a historic expression; the States originally comprised the constables and rectors of the 12 parishes and 12 jurats. Until legislative changes in 2005, the “States of Jersey” was the corporate body that was covered by the parliament and the government. The expression “States of Jersey” is used at various times to describe the government, the parliament, and the Island. For the purposes of understanding the internal political system it is easier to refer simply to the government and to the States Assembly.

Jersey’s political system does not fall into any of the simple categories noted in the previous section. It has some distinctive features that are shared only by other relatively small states. The key features are –

- A single chamber parliament – the States Assembly, but with (very unusually) two different types of members: deputies elected for constituencies based on population and the constables of each of the 12 parishes whose main responsibilities relate to their parishes. Until the 2022 election, there were three categories of member, with eight senators elected on an Island-wide basis, as well as constables and deputies. From the 2026 election, with the island-wide position of senator being reinstated, there will be three categories of member, as there were prior to 2022.

- The Chief Minister is elected by the members of the Assembly. As most members are elected as independents, the Chief Minister is the person who can command the most support from all the members of the Assembly. So, unlike in British elections, the electors are voting for individuals rather than a party whose leader wishes to be Chief Minister. The Chief Minister nominates Ministers, but it is open to the Assembly to reject those nominations, and it has done so in the past.

It is the absence of political parties, or a tradition of non-partisan politics, that is the key feature of the Jersey system. There is no legal rule that forbids political parties or forces candidates to be independent, nor do elections (which follow the "first past the post" system) force candidates to be independent either. The law specifically provides for parties, and four political parties had candidates in the 2022 election. The legal position is no different from that in Britain but there the custom is for people to vote for parties, not individuals, and campaigns are fought between parties. In countries where there is proportional representation, for example, Scotland, then in effect there has to be political parties.

It is worth noting the position in the other two crown dependencies –

- Guernsey has a single chamber parliament, the States of Deliberation. Until the general election in 2020, 45 members were elected in seven constituencies based on the number of electors. Following a referendum, the system was changed such that in 2020 and 2025 there was a single constituency. In the 2025 election, 82 candidates stood for 38 seats (in addition, Alderney elected two representatives). As each elector had 38 votes but there was no transferable vote system, the 38 candidates with the most votes were elected. Like Jersey, Guernsey had previously elected independents rather than parties. In the 2020 election, 40 of the 119 candidates stood for one of three parties. 16 of the successful candidates were from parties, with the remaining 22 being independents. In the 2025 election, five candidates stood for the Forward Guernsey party, three of whom were elected. Following the election, the States elected the highest polling candidate as Chief Minister. A special feature of Guernsey’s system is that the government is run through committees rather than Ministers.

- The Isle of Man has a bicameral system. The Tynwald has two chambers – the House of Keys with 24 members for twelve two-seat constituencies and a Legislative Council with eight members elected by the House of Keys and three ex officio members. Parties have a minimal role. The members of the House of Keys elect a Chief Minister who in turn appoints Ministers.

Jersey’s parliamentary system

Jersey has a single chamber parliament, the States Assembly, although often it is simply called “the States”.

Jersey’s parliamentary arrangements are set out primarily in four laws –

- The States of Jersey Law 2005 provides for the composition of the States Assembly, the four-year election cycle, and the qualifications for standing for election.

- The Elections (Jersey) Law 2002 sets out provisions for the conduct of elections.

- The Political Parties (Registration) (Jersey) Law 2008 covers requirements for political parties.

- The Public Elections (Expenditure and Donations) Law 2014 deals with controls on election expenditure.

The composition of the States Assembly

Prior to the 2022 election and with effect from the 2026 election, the elected members comprise the constables of each of the Island’s 12 parishes, senators elected on an Island-wide basis, and deputies elected by constituencies based on parishes. As members of the Assembly, constables, senators and deputies are equal in that each member has one vote and each is able to be a minister. However, in practice there are differences –

- The constables’ primary responsibility is for their individual parishes and most of their work is in that capacity. Their role as members of the Assembly is secondary. Some constables choose to play a modest role in the Assembly, by serving on scrutiny panels, always attending and voting. A few want to be involved in government and can be appointed as ministers or assistant ministers.

- Senators are not currently in the Assembly, but the position has been reinstated for the 2026 election. As they are elected on an island-wide basis the elections concentrate on island-wide issues rather than parochial issues. Senators are regarded as the “senior” members. The Chief Minister will almost certainly be a senator and most of the senators will be in the Council of Ministers.

- Deputies are elected at the local level and together with constables will be particularly involved in issues affecting individual parishes. However, some are also very active at the island-wide level and seek to serve in the government or play a major role on committees.

All elections are on the “first past the post” system, in which the candidate or candidates with the highest number of votes are elected.

Two main deficiencies were apparent with this system prior to the 2022 election –

- A single chamber parliament with three different types of members is, by any standards, unusual.

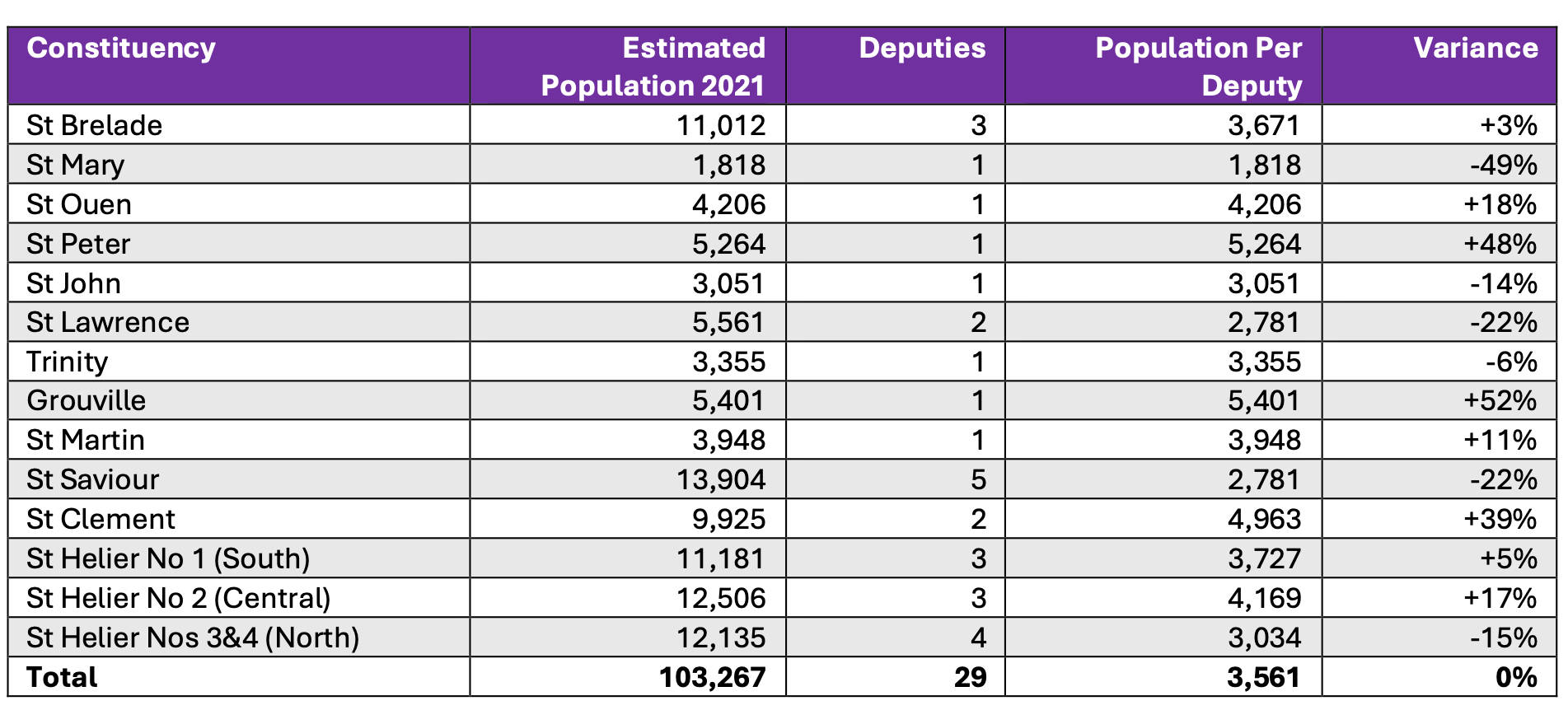

- With constituencies based on parishes, the system resulted in huge geographical variations in the population per elected representative. This is illustrated in Table 1 which shows the position for deputies prior to the 2022 election.

Table 1 Constituencies for Deputy prior to the 2022 election

Notes:

1. The population figures are from the report Population by electoral district (Statistics Jersey, 2022).

2. St Saviour was divided into three districts and St Brelade into two. They have been aggregated in this table.

3 . St Helier was divided into three districts which do not exactly correspond to the districts in the 2022 election but are sufficiently aligned for the purposes of the comparison.

4. The variance column shows the population per deputy figure in relation to the average for the Island of 3,561.

5. In the variance column a minus figure indicates that the district was over-represented compared with the average and a plus figure that it was under-represented.

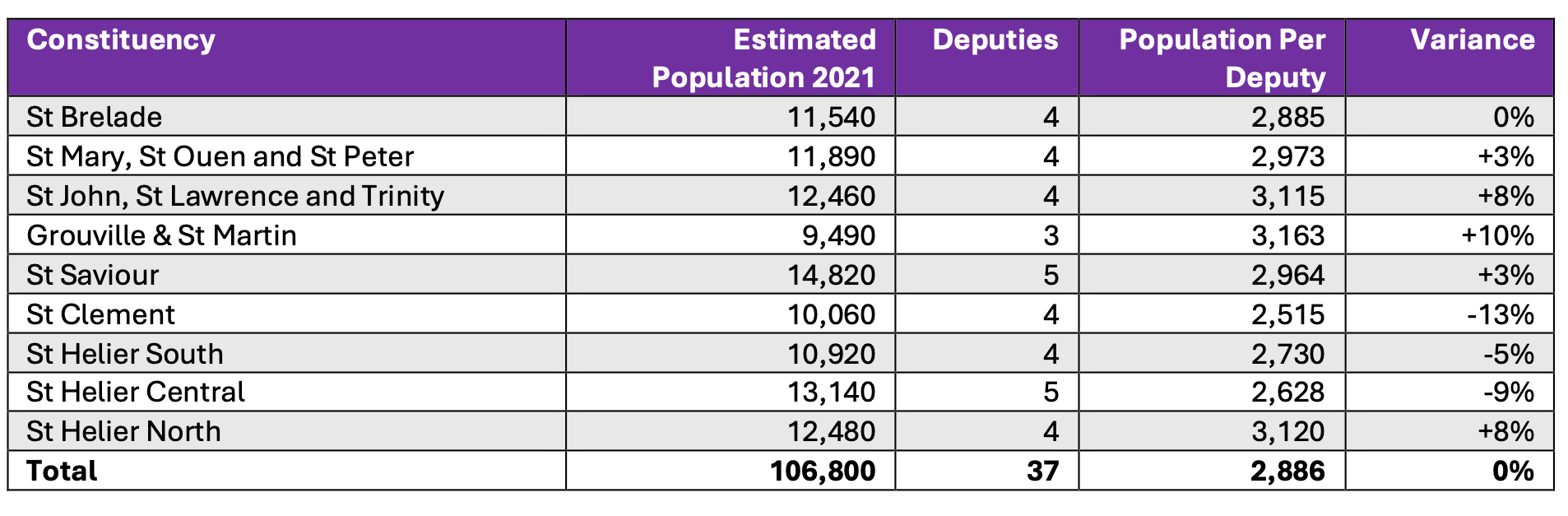

The solution adopted for the 2022 election was to reduce the number of constituencies from 14 to 9 and given that there was an increase in the number of deputies, this facilitated a more even distribution of the constituencies in respect of population per deputy. Table 2 shows the new constituencies, the data being taken from the table in the proposition on constituencies agreed by the States Assembly.

Table 2 Constituencies for the 2022 election

Notes:

1. This table uses the estimated population at the end of 2019 rather than the figure in Table 1, which are based on the actual population according to the 2021 census.

2. In the variance column a minus figure indicates that the district was over-represented and a plus figure that it was under-represented.

It was regarded as sacrosanct that constituencies should not cross parish borders and, for this reason, there are still some variations in respect of population per deputy. For example, St Clement is the outlier with over-representation of 13%. But if its number of deputies was reduced to three, then it would be under-represented by 16%. In other states, the solution would have been to move some voters from St Clement to Grouville/St Martin purely for the purpose of the elections of deputies, but maintaining constituencies based on parishes meant that this was not possible. However, the range of variance from the norm of +10% to -13% was much lower than the figures of +52% to -49% with the previous system.

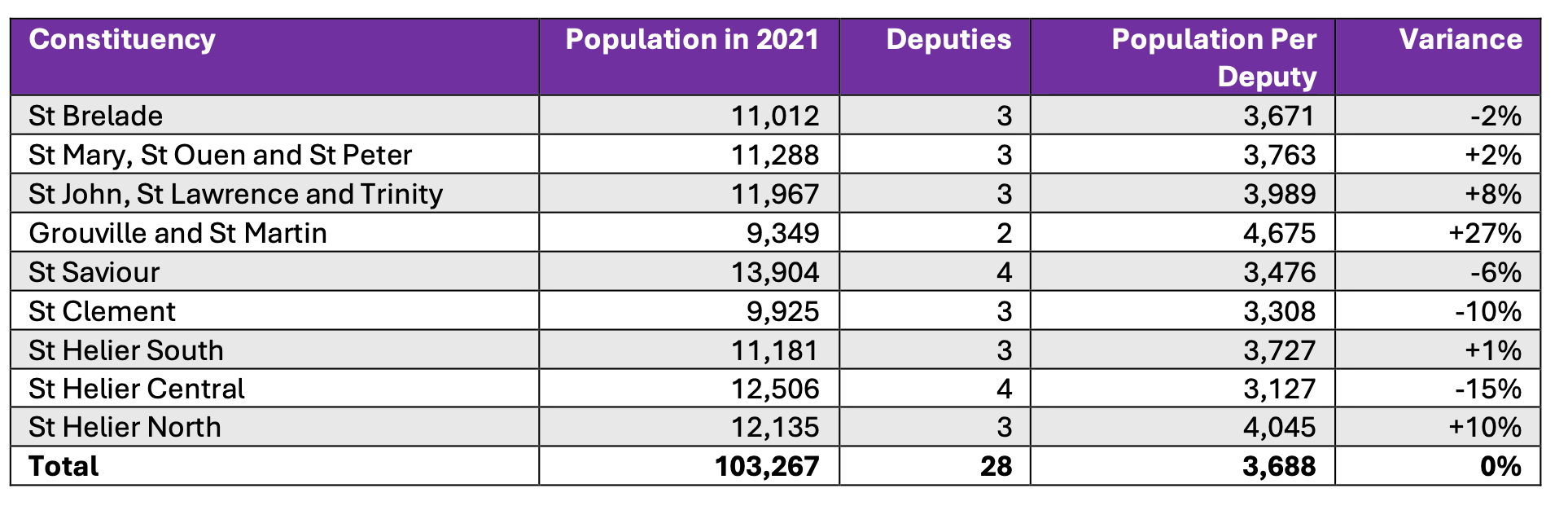

The States Assembly decided in September 2025 to reinstate the position of Senator with effect from the 2026 election. Nine senators will be elected on an island-wide basis. To maintain the size of the Assembly, one deputy is being removed from each of the nine constituencies. This significantly alters the population distribution per deputy as Table 3 indicates.

Table 3 Constituencies for the 2026 election

Notes:

1. The population figures are from the report Population by electoral district (Statistics Jersey, 2022).

Two constituencies, Grouville/St Martin and St Helier Central, exceed the 15% limit which the Venice Commission Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters states should “never” be passed and two others, St Clement and St Helier North, are at the 10% benchmark. The range of variation from the norm has increased from +12% to -10% to +27% to -15%, and the average variation from the norm has increased from 5.6% to 9.0%.

The States of Jersey Law 2005 and the Elections (Senators) (jersey) (Amendment) Law 2025 make the following provisions for the composition and functioning of the States Assembly. It should be noted that the law refers to “the States” rather than the Assembly.

- Article 2 provides that the States is constituted with 37 deputies and the 12 parish constables, and with effect from the 2026 election, nine senators, 28 deputies and 12 parish constables. The Bailiff, the Lieutenant Governor, the Dean of Jersey, the Attorney General and the Solicitor General as ex officio members. They have the right to speak but not to vote and by custom do not speak except in their official capacities. For practical purposes, the Assembly can be regarded as the 49 elected members.

- Article 3 provides that the Bailiff is the President of the States, in effect the speaker responsible for the conduct of meetings.

- Article 3A provides that for the election of senators the 12 parishes are a single constituency.

- Article 3B provides for the constituencies for deputies and the number of deputies in each constituency, which are set out in Schedule 1.

- Article 6 provides that elections shall be held every four years.

- Article 7 sets out the qualifications for election as Deputy or Senator, basically a British citizen who has been ordinarily resident in Jersey for at least two years up to the date of the election or ordinarily resident for six months up to the date of the election and for additional periods at any time of at least five years.

- Article 41 provides for there to be a Greffier of the States who is the clerk to the States, in effect the chief executive of the States Assembly.

- Article 42 provides for a Viscount who has some responsibilities for law enforcement.

- Article 44 provides for the remuneration of elected members with an important proviso that all members must receive the same remuneration.

The operation of the States Assembly

All parliaments have a system of committees with responsibilities, including holding Ministers to account, considering procedures and scrutinising legislation. Such committees are provided for in the Standing Orders of the States Assembly -

- The Privileges and Procedures Committee has wide-ranging responsibilities including the conduct of the States Assembly, elections and the provision of services for members. It also provides information to the public about the work of the States Assembly, the Council of Ministers, the scrutiny panels and the Public Accounts Committee. This is a significant committee, the chairmanship of which is regarded as one of the most important non-ministerial positions.

- The Public Accounts Committee holds responsibility for financial audits and efficiency reports, working with the Comptroller and Auditor General.

- The Planning Committee considers applications for property and land development and grants or refuses planning permission.

- Scrutiny panels, which are empowered to hold reviews on subjects within their terms of reference, consider the policy of the Council of Ministers, and scrutinise laws, the government plan and other financial proposals of the Council of Ministers. Five panels currently exist –

- Corporate Services.

- Economic and International Affairs.

- Children, education and home affairs.

- Environment, Housing and Infrastructure.

- Health, social services and social security.

- The Scrutiny Liaison Committee comprises the chair of the Public Accounts Committee and the chair of each scrutiny panel. The president of this committee is selected by the States Assembly and can be seen as the “chief scrutineer” of the government.

- Review panels established for a specific purpose.

More generally, the Standing Orders prescribe in considerable detail the conduct of business in the States Assembly. They give considerable power to individual members.

Particularly significant are the provisions in relation to propositions, which can be for a new law, policy or action. A proposition can be lodged by ministers, committees and individual members. Paragraph 21 of Standing Orders requires that a proposition -

must be accompanied by the proposer’s statement of whether the proposition, if adopted, would have any implications for the financial or manpower resources of the States or any administration of the States and, if there are such implications –

(a) set out the proposer’s estimate of those implications; and

(b) explain –

(i) how the proposer has calculated his or her estimate of those implications, and

(ii) how, when and from where, in the proposer’s opinion, they could be sourced.

The proposer may request information from any Minister responsible for the resources in question and a Minister shall, when so requested, ensure that the proposer is provided with complete and accurate information sufficient to enable the proposer to prepare the statement.

The draft may be accompanied by a report setting out why the proposer considers that the proposition should be adopted.

It is noted that there is no requirement for the proposition to state the impact on the public and that proposers only “may” set out why the proposition should be adopted. All propositions are then debated.

Paragraph 63 provides that at each sitting of the Assembly up to 2 hours and 20 minutes shall be allowed for questions of which notice has been given, and paragraph 64 provides that up to 45 minutes must be allowed for questions without notice.

Paragraph 104A provides that any member may speak for up to 15 minutes in a debate.

The States Assembly Annual Report 2024 outlines in detail the Assembly's work during that year, including details of major debates and a comprehensive analysis of questions asked, as well as the work of scrutiny panels and committees. Some key facts -

- The Assembly sat on 36 days.

- Just over 65% of the Assembly’s time was spent on “public business”, largely debating propositions and legislation, and 23% was spent on questions. The time spent on public business represents a decline from previous years.

- 17 draft laws and 17 sets of regulations were debated.

- 89 propositions were brought, most by ministers but 26 by individual members.

- There were 247 oral and 440 written questions.

More generally the Report provides the best official description of the structure and functions of the Assembly.

Elections

The Elections (Jersey) Law 2002 governs the conduct of elections. The law includes very detailed provisions on the conduct of the elections. The main points are -

- Article 5 provides that a person is entitled to be on the electoral register if they are at least 16 years old, resident in the district of the election and have been ordinarily resident in Jersey for a period of at least two years up to and including the day they register or ordinarily resident for at least six months up to and including that day as well as having been ordinarily resident at any time for additional periods of at least five years.

- Article 6 provides that electoral registers are to be maintained by each parish.

- Article 13A establishes the Jersey Electoral Authority (JEA). The schedule to the law provides that the JEA comprises a chair, between two and four ordinary members, a parish representative member and, ex officio, the Judicial Greffier and the Greffier of the States. The JEA is responsible for overseeing the conduct of elections and is required to provide a report on each general election.

- Article 13C provides for the JEA to prepare and publish a code of conduct for candidates in elections.

- Articles 17C, D, E and F set out requirements for nomination, including the content of the nomination form, a requirement that nomination forms be subscribed by a proposer and nine seconders who are entitled to vote in the election, and a political party declaration for those candidates supported by a political party.

- Article 24 prescribes the content of ballot papers.

- Article 24(3C)(b) provides that where the number of vacancies for the office is equal to, or exceeds, the number of candidates, electors have the option of voting for none of the candidates.

- Article 25 requires that each election should be by secret ballot.

- Article 26 requires each parish to provide one or more polling stations in such a way “that all persons have reasonable facilities for the exercise of the right to vote”.

- Article 38 makes provisions for pre-polling, that is submitting a ballot paper in advance of the election date, and for postal voting. Anyone is entitled to a postal vote by making an appropriate application.

Article 24(3C)(b) is particularly significant as it was an innovation and one that is uncommon in other jurisdictions. It provides that where an election would otherwise be uncontested then there is an election in which electors can vote for or against the nominated candidate or candidates.

The Connétables (Jersey) Law 2008 makes provision for the election of constables (connétables), largely replicating the provisions for the election of deputies.

The Public Elections (Expenditure and Donations) (Jersey) Law 2014 governs election expenditure and donations to parties and candidates. The key provisions are –

- Expenditure during a “regulated period”, the period beginning four months before election day, is covered by the provisions.

- “Election expenses” are defined in Article 3(1) of the Law as expenses incurred at any time before the poll for that election

- (a) by the candidate, or with the candidate’s express or implied consent; and

- (b)for the supply or use of goods, or the provision of services, which are used during the regulated period –

- (i)to promote or procure the candidate’s election, or

- (ii) to prejudice the electoral prospects of another candidate at the same election.

- The expenditure limits are £2,517 plus 13 pence for each elector in elections for deputy and constable (in round terms about £3,500 for a deputy election and between £2,700 and £4,700 for a constable election), and £4,416 + 13 p for each elector (in round terms about £13,500) for a senator election.

Political parties

There is provision for political parties in Jersey under the Political Parties (Registration) (Jersey) Law 2008. This sets out requirements for a party to be registered. In an election, candidates endorsed by a registered political party have the party affiliation alongside their name on the ballot paper. In recent elections, the vast majority of members have been elected on an individual basis. Four political parties contested the 2022 election. Between them, they won 13 of the 37 deputy seats and one constable position. Reform Jersey, with ten deputies, is the only party with significant representation in the Assembly. The operation of the States Assembly does not recognise parties.

The Jersey Government

The States of Jersey Law 2005 covers the Government of Jersey as well as the States Assembly.

Article 18 of the Law has the following key provisions –

- There shall be a Council of Ministers comprising a Chief Minister and at least seven Ministers.

- The Council of Ministers must lodge a statement of its common strategic policy and government plan within four months of taking office.

Article 19 provides that -

- The States Assembly must select an elected member as Chief Minister after each ordinary election for deputies and in other circumstances such as the resignation of or vote of no confidence of the Chief Minister.

- The Chief Minister must nominate elected members for appointment as Ministers and the office they will hold, but other members can also nominate alternative candidates for each Ministerial position.

Other significant provisions are –

- The Chief Minister is required to appoint one of the Ministers as Deputy Chief Minister.

- The Chief Minister and Ministers may appoint one or more elected members as Assistant Ministers.

- The aggregate of the Chief Minister, Ministers and Assistant Ministers must not exceed a limit set out in standing orders (currently 21).

- Ministers may delegate functions to one or more of their Assistant Ministers or an officer.

- Article 18 (2A) of the Law requires the Council of Ministers to lodge the statement of their common strategic policy.

The Public Finance (Jersey) Law 2019 sets out detailed provisions in respect of the public finances and is very prescriptive in a number of respects. Provisions include –

- Article 9(1) requires that “Each financial year, the Council of Ministers must prepare a government plan and lodge it in sufficient time for the States to debate and approve it before the start of the next financial year”.

- Article 9(5) requires that a government plan cannot show a negative balance in the Consolidated Fund (basically the fund for current income and expenditure) at the end of any of the financial years covered by the plan.

- There are provisions for a strategic reserve, a stabilisation fund and other reserves.

- Article 37 provides for the accounts to be prepared within three months of the end of the year and to be sent to the Comptroller and Auditor General for auditing.

The parishes

Jersey has 12 parishes, which play a significant part in the life of the Island. Their boundaries were established about a thousand years ago and each of the parishes has a distinct identity with which people identify. The parishes each have at least one primary school, and some sporting activities, in particular football, have a structure based on the parishes. In some of the country parishes, there is a clear centre of the parish, with the parish church, the parish hall, a pub and shops.

The parishes have responsibility for some activities that might otherwise fall to the Island’s government, including refuse collection, care of the roads and some licensing. The principal officer of the parish is the constable (also referred to using the French word Connétable), who by virtue of that office is also a member of the States Assembly. The constables are elected at the general elections, held every four years, the electorate being residents of the parish. Each parish has two procureurs de bien public, elected at parish assemblies, who act as public trustees. They maintain an oversight of parish finances and represent the parish in the care of parish property. Each parish also has a roads committee and roads inspectors.

The parish assembly is an integral part of the way the parishes operate. People registered as electors in public elections, as well as ratepayers, are entitled to attend assemblies. The parish assemblies elect the officers (other than the Constable), and are responsible for the care of the roads, the promotion of local improvements, for setting rates and considering licensing applications.

More importantly, in respect of the political system of the Island, is the role that the parishes play in the States Assembly. That role is lessened after the 2022 reforms, but the constituencies for deputies are still parish-based. More importantly, each of the 12 constables is, by virtue of the role, a member of the Assembly with the same rights and responsibilities as other members, which means that the parishes with smaller populations are better represented. The bulk of the work of the constables is at the parish-level, so their status is an unusual one. The workload is such that the position has become less attractive, with most elections for constable being uncontested. On average, the constables are less involved in the Assembly and government than other members. At present, only two constables are members of the Council of Ministers, and two are assistant ministers.

Given that the States Assembly is unusual in having two separate categories of member, the presence of constables benefits the smaller parishes in terms of representation, and that the bulk of the constables’ work is in their parishes and that therefore they are less involved in the work of the Assembly, the question of whether the constables should remain in the Assembly is regularly raised. The Clothier Report (see final section) could see no difference in the role which constables and deputies had in the Assembly and accordingly it recommended that constables should no longer be by virtue of the office members of the States Assembly but should be free to stand for election as deputy. However, in a referendum in 2013 on the composition of the Assembly there was a preference for constables remaining members of the assembly.

The constables have their own committee, the Comité des Connétables, whichconsiders issues of interest to the constables and their parishes.

Legislation

Laws are made in Jersey in much the same way as in other places. The legal provisions on legislation are set out in the Legislation (Jersey) Law 2021 . Most proposals for a law are made by the government, but individual members of the States Assembly are also able to propose a new law or an amendment to an existing law. Prior to a law being drafted, there may have been an extensive period of preparation and public consultation and possibly consultation on a draft of the proposed law. This process aims to ensure that the implications of what is being proposed are assessed and understood.

The first formal stage is for the proposal to be lodged in the States Assembly. It is at this stage that the full text of the proposed law is made public. There are then a number of opportunities for it to be to be debated by the States Assembly and for amendments to be proposed and considered. The States Assembly approves the final version, which is then submitted to the Ministry of Justice in the UK for formal approval by the Privy Council. This is normally done as a matter of course as the officials in Jersey ensure that there is nothing in the law that would conflict with the UK’s international obligations. The law is then formally registered by the Royal Court in Jersey. A new law does not normally come into effect immediately, but rather on days either specified in the law or made under provisions in the law. This is to give ample opportunity for any necessary new arrangements to be put into place and for those specifically affected by the law to have due notice of it.

The Jersey Legal Information Board website has a comprehensive database of all current and pending laws.

The political system in practice

There has been concern about the operation of the political machinery in Jersey and there have been a number of attempts at reform. The most significant was the “Clothier Review”. In 1999, the States Assembly commissioned a body “to undertake a review of all aspects of the Machinery of Government in Jersey”. This body had wide-ranging terms of reference, including the composition of the States Assembly. Chaired by Sir Cecil Clothier, former Parliamentary and Health Services Ombudsman and first Chair of the Policy Complaints Authority, the body produced a comprehensive report in December 2000. Much of the analysis in the report, particularly by comparing the position in Jersey with that in other jurisdictions, remains valid today. The report noted that “the electorate of Jersey has become apathetic, disenchanted with, and detached from its government”. It also presented a critical view of the performance of the Assembly, in particular the lack of effective use of the time available with too many repetitive speeches by too many members. It made a number of recommendations on the constitution of the Assembly –

- It could see no significant difference between the role of senator and the role of deputy and accordingly recommended the abolition of senators with an additional 12 deputies.

- It could see no role in the Assembly of constable that was different from that of deputy, and accordingly it recommended that constables should no longer be ex-officio members of the States Assembly but should be free to stand for election as deputy.

- It recommended an Assembly of between 42 and 44 deputies, which would produce “a much more even distribution of seats per elector” than was achieved by the system then in operation.

- The Bailiff should cease to be President of the Assembly.

The report did not find favour in the Assembly, and none of these recommendations on the constitution of the Assembly were implemented. However, its recommendations on the government and on many other matters were largely implemented and subsequently the role of senator was abolished, although now reinstated, and a more even distribution of seats per elector has been established.

While legislation is important in determining how a political system works, custom, practice and personal preferences also play a significant part. To understand the Jersey system in practice, it is helpful to note some key issues arising from the general election in June 2022 and the subsequent constitution of the States Assembly.

The turnout in the 2022 general election was very low at 41.7%, a fall of nearly two percentage points from the figure in the previous election and well below the target of 50% that had been set by the States Assembly. Turnout in Jersey general elections has consistently been among the lowest of all OECD jurisdictions, roughly 30% below the average.

Of the 12 constables, eight ran unopposed, and therefore had to face an election against “none of the above”. In two of the constituencies, there was an organised campaign for “none of the above”, which secured votes of 43% and 27%. 11 of the constables were elected as independents and one as a representative of a political party, from which he resigned on taking office.

All of the nine new deputy constituencies had contested elections, a total of 76 candidates competing for 37 seats. The successful candidates were made-up as follows –

- 24 independents

- 10 members of the Reform Jersey party.

- Three members of other parties.

With the 11 constables elected as independents, and one becoming an independent soon after, this meant that 36 of the 49 members were independents.

With this result, Jersey could not have a party-based system either in the government or the Assembly. In the contest for Chief Minister, an independent member, Kristina Moore, defeated the Leader of the Reform Jersey party. She in turn nominated 12 members, all elected as independents, to be Ministers in the Council of Ministers, the portfolios being Economic Development, Tourism, Sport and Culture; External Relations and Financial Services; International Development; Infrastructure; Social Security; Children and Education; Home Affairs; Treasury and Resources; Health and Social Services; Housing and Communities; and Environment.

In January 2024, Kristina Moore lost a vote of no confidence, and her Council of Ministers therefore also fell. In the contest for Chief Minister another independent member, Lyndon Farnham, defeated the Leader of the Reform Jersey party and another independent member. He in turn nominated 12 members to the same portfolios, although with the intention that the previous Children and Education portfolio would be split into separate portfolios: children, and education and lifelong skills. Three of the nominated ministers were members of the Reform Jersey party, one a former member of the Progress party, and the others were independents.

It is relevant to note here two other significant features of the way that the system operates –

- There is no collective responsibility for Ministers, meaning that they can criticise policy and speak out against each other.

- The standing orders provide that any member may bring forward a proposition to the States Assembly and that it has to be considered.

The combination of all of these factors means that, unlike Westminster the government is in a relatively weak position in relation to the parliament. Not only does it not have a majority, but its members are not bound by collective responsibility and indeed can legitimately point out that they were elected as independents and should act as such. The system also gives individual members the ability to pursue their own issues and to make life difficult for the government, in particular because a significant amount of time is allowed for oral questions and debate. Ministers cannot be certain that their policies will be approved by the Assembly and also have to face the possibility that the Assembly will agree laws and policies to which they are opposed. This can, of course happen, in other parliaments as it has done from time to time in the British parliament, but the point about the Jersey system is that these processes are built in.

The composition of the Assembly, the electoral system, and the machinery of government are likely to continue to be on the agenda. Key issues are seen as being –

- Whether constables should remain as members of the Assembly.

- Whether the Bailiff should continue to be the President of the Assembly.

- The low level of turnout in elections – an issue covered in the Policy Centre report Election turnout in Jersey.

- The low degree of trust in the political system – an issue covered in a Policy Centre think piece Restoring trust in Jersey politics.

Sources of further information

Understanding Jersey’s political system is difficult for two main reasons –

- The use of the expression "States of Jersey".

- Key documents explaining political decisions are not easily accessible. Typically, they are buried in a proposition to the Assembly and are described by a number rather than by name. There is little attempt to publish key reports separately in a way that enables them to be easily identified and accessed. See for example the reference below to the important report Electoral reform 2020 which can be found only by people who know exactly what they are looking for.

Laws

Up-to-date versions of laws are published on the Jersey Legal Information Board website. The four key laws are –

- The States of Jersey Law 2005, the key law on Jersey’s political system, covering both the Assembly and the government.

- The Elections (Jersey) Law 2002 sets out provision for the conduct of elections.

- The Political Parties (Registration) (Jersey) Law 2008 covers requirements for political parties.

- The Public Elections (Expenditure and Donations) Law 2014 deals with controls on election expenditure.

Operation of the States Assembly

The States Assembly website provides detailed information on all aspects of the States Assembly. The States Assembly Annual Report 2024 is particularly informative. A key constitutional document is the Standing orders of the States of Jersey.

Reports on Jersey’s political system

Democratic Accountability and Governance Sub-Committee Report, 18 February 2022, R.23/2022. (Notwithstanding the absence of a title and inaccessibility, this report provides a good description of Jersey’s political system and particularly of how the government is held accountable.)

Electoral reform 2020. Report lodged on 23rd December 2019 by the Privileges and Procedures Committee, P.126/2019. (This is the substantive report on the changes to the composition of the States assembly in 2022. It contains much useful analysis.)

Jersey General Election 2018, CPA BIMR election observation mission final report.

States of Jersey General Election June 2022, CPA BIMR election observation mission final report.

(The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) London in its role as secretariat for CPA's British Islands and Mediterranean Region (CPA BIMR), carries out and supports election observation work across the Commonwealth. CPA BIMR is specialised in election observation work in UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It sends observers to elections and subsequently publishes reports.)

Christopher Pich and John Reardon, A changing political landscape: the 2022 general election in Jersey. Small States and Territories Journal, 6 (2), 2023.

Mark Boleat, Jersey’s 2022 general election.

Mark Boleat, Election turnout in Jersey, Policy Centre Jersey, 2026.

Report of the review panel of the machinery of government in Jersey (the Clothier report) (2000). The review panel was established by the States Assembly to review all aspects of the machinery of government in Jersey. The authoritative report is the only substantial external review of the machinery government. Most of its substantive recommendations were not implemented.

Other jurisdictions

Isle of Man General Election 2021, CPA BIMR election observation mission final report.

Guernsey General Election 2020, CPA BIMR election observation mission final report.

Guernsey General Election 2025, CPA BIMR election observation mission final report.

John Reardon and Christopher Pich. The strangest election in the world? Reflecting on the 2020 General Election in Guernsey. Small States and Territories Journal, 4 (1), May 2021.