Research

The construction industry in Jersey

Introduction

The JCRA has commissioned the Policy Centre Jersey to undertake a largely desk-based study to describe and analyse the construction sector in Jersey. This report is based on published material, supplemented by informal confidential discussion with two industry stakeholders.

It is important to note that there is very little published information on the construction industry in Jersey. The only published statistics are in the decennial census and aggregate figures for contribution to economic activity and composition of the labour force. There are no specific construction statistics so it is not possible to breakdown activity between housing, offices and infrastructure for example. There are also no statistics available on housebuilding. With respect to company data, there is no information other than what those companies choose to publish. This paper includes all of the available statistics.

Summary

There are three main groups of participants in the construction process: the client, the main contractor and subcontractors. However, there are any number of variations on this basic structure including design and build, joint ventures and the developer also being the contractor. Some main contractors undertake the construction work themselves while others rely heavily on subcontractors. And contractors vary the use they make of subcontractors so as make the most efficient use of their resources.

Both construction and development activities are inherently risky, particularly because of planning risks and the relatively long time frame from conception to completion of a project. Various techniques are used to mitigate these risks.

In 2022 the construction industry accounted for 7.3% of economic activity and just under 10% of employment in Jersey. The industry is a larger component of the economy than it is in Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK.

The major developers are the Government of Jersey, Andium Homes (the Jersey’s Government’s social housing provider), the (Government-owned) Jersey Development Company, and two private companies: Dandara and Le Masurier. However, the largest component of construction demand is capital improvements by home owners.

The construction industry has nearly 1,500 businesses over half of which are one-person businesses. 10 companies employ 50 or more staff.

The major contractors are Dandara, for its own developments but also for other clients, Rok and Legendre. There are many smaller general contractors and specialist service and equipment providers. Companies specialising in home improvements are particularly prominent. Local companies also supply raw materials, in particular concrete, aggregates and stone surfaces. UK-based contractors and workers also operate in Jersey.

Improvements by home owners account for about 30% of total construction activity. Social housing, private housing and commercial developments show significant year-to-year variation but on average each accounts for 15-20% of total activity. Infrastructure and health and education facilities have a base expenditure of around 10% of the total but the new hospital will massively increase that proportion in 2026 and 2027. Repairs and maintenance account for about 10-15% of the total.

The vast majority of all construction work is handled on-island by local firms. Off-island contractors are most likely to be employed for major contracts or highly specialised services. However, the market economy is such that UK contractors and individual workers are able to operate in Jersey with little difficulty and both help fill gaps in the supply chain and exert competitive pressure on local companies.

Special factors affecting the construction market in Jersey are that it is a small island and a separate legal jurisdiction, the dysfunctional planning system, articulated in the 2023 McKinnon Report, and the government being unpredictable in respect of its own developments.

The industry currently identifies input prices, profitability and low capacity utilisation as being major issues .

An overview of Jersey

It is helpful to note the characteristics of Jersey that are relevant to the operation of the construction market. Jersey is a small island, geographically part of France, 120 square kilometres, with a population of a little over 100,000. It is a British crown dependency that for all practical purposes has complete internal self-government. In practice, there are very close links between Jersey and the UK and many economic activities in Jersey are functionally integrated into the UK. However, the following points are relevant to the construction industry:

- The small size of the island combined with the need for most building materials to be imported by ferry.

- The island has its own taxation, regulation, health and safety and employment laws.

- The island has its own planning system although it operates in similar ways to the system in England.

- Jersey needs to provide infrastructure that would not normally exist for a community of 100,000 including a major port, a major airport, a hospital and utilities.

- Jersey is a distinct unitary legal entity, the government and parliament, the States Assembly, covering issues that in the UK would be handled separately by the national government, and where they exist devolved assemblies, metro mayors, unitary authorities, county councils and district councils.

The nature of the construction industry and market

There is ample scope to debate what should and should not be included within the definition of the construction industry. Under the 2007 Standard Industrial Classification the construction industry comprises –

- Construction of buildings

- Development of building projects

- Civil engineering

- Construction of roads and railways

- Construction of utility projects

- Specialised construction activities

- Demolition and site preparation.

- Electrical, plumbing and other construction installation activities

- Plumbing, heat and air condition installation

- Building completion and finishing.

Activities closely connected with construction that do not come within this definition include –

- Wholesalers of timber and building supplies

- Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis

- Renting and leasing of construction and civil engineering machinery and equipment

- Provision of labour.

Mining and quarrying are a separate classification. However, in Jersey the statistics for construction and for mining and quarrying are combined.

The total volume of construction activity in a relatively small market is “lumpy”, reflecting not so much construction itself but rather the whole development process. Large projects in particular have a long gestation period from conception to completion, with the actual construction phase being a relatively small proportion of the total. This means that demand for particular aspects of construction, such as demolition or fitting out, can be very variable. A contractor, even with a steady flow of work, needs a regularly changing mix of skills and equipment. For this reason the delivery function tends to be fragmented with a large number of specialist contractors working on a development at different times.

The main participants in the construction market are –

- The client. For major projects the client is a developer, taking the risks and receiving the profit. The developer’s role includes acquiring the land, securing planning permission, designing the building for which an architect, and sometimes other specialists, are typically employed, commissioning the construction, overseeing the construction contract and selling or managing the completed development. However, for much work the client is an individual commissioning home improvements or repairs.

- Main contractors. The client selects the contractor. There are several different ways in which is done –

o For very large contracts, for example the new government headquarters or an office block in the International Finance Centre, a formal tender process is likely to be used.

o A developer of a large project knows at the outset roughly what a project should cost and equally is familiar with potential contractors. For this reason a developer may choose to negotiate a contract with a contractor, the process avoiding the cost and time involved in a formal tender process.

o Where a property owner has many properties and other assets that require regular repairs and maintenance the normal practice is to negotiate a term contract, typically by tender, under which the contractor undertakes a large number of individual projects under an agreed schedule of prices.

o An individual commissioning improvements or repairs to their home may use an architect or surveyor to plan the project and retain the contractor or may negotiate directly with a contractor.

- Sub-contractors, who are employed by the main contractors for specialist activities. Some contractors prefer to do as much as possible with their own staff whilst others concentrate on their core activity and subcontract much of the work.

There are any number of variations on this basic structure. In particular –

- Some companies combine development and contracting.

- In some cases a contractor is commissioned on a “design and build” basis, undertaking much of the work that the developer would normally do.

- A developer and a contractor may set up a joint venture, the contractor sharing some of the development’s financial risks and rewards.

One large contractor may use all of these models for different contracts – undertaking a design and build contract for one developer, undertaking most of the contracting work for another and being little more than a project manager for a third, the contractor endeavouring to make the most efficient use of their resources.

The model used will depend on the circumstances of the market and the individual companies at the time. For example, an office developer may be confident of being able to develop a small office on its own but for a very large office may prefer a design and build contract or joint venture. A large developer of housing which prefers to use its own contracting services may employ external contractors on specific projects as a means of managing its resources.

Both construction and development activities are inherently risky for a number of reasons –

- In the case of development, planning risks. Where the planning system in a jurisdiction is unpredictable or where the process is a lengthy this imposes a substantial risk to the developer.

- The relatively long time frame from conception to completion, heavily dependent on the planning process, increases the risk of the market moving in a way that was not forecast at the outset.

- Some projects, particularly those involving redevelopment rather than building on a greenfield site, run the risk of unexpected problems that cause increases in cost.

The risky nature of construction activity means that some developers, contractors and subcontractors can quickly go out of business. This imposes risks for the client who has to replace their contractor and also for any contractors or subcontractors who may well lose money. In Jersey in 2023 one of the largest contractors, Camerons, went into liquidation followed by JP Mauger, and in 2021 the major UK construction firm, NMCN, went into liquidation while undertaking the £75 million sewage treatment plant project.

To mitigate the risks, market participants use a number of different techniques –

- Extensive due diligence on contractors and subcontractors.

- Joint venture arrangements.

- Selling developments off-plan or at an early stage of the construction process so as to reduce the risk resulting from adverse market movements.

- Project management to ensure that the contract runs smoothly.

- Insurance arrangements, typically in the form of a bond to compensate a client in the event of a contractor not being able to complete a contract.

The construction industry in Jersey – importance in the economy

The published Jersey statistics have a category of “construction, quarrying and mining”. There is no breakdown between these three categories but as set out this report, the vast majority of this category is construction.

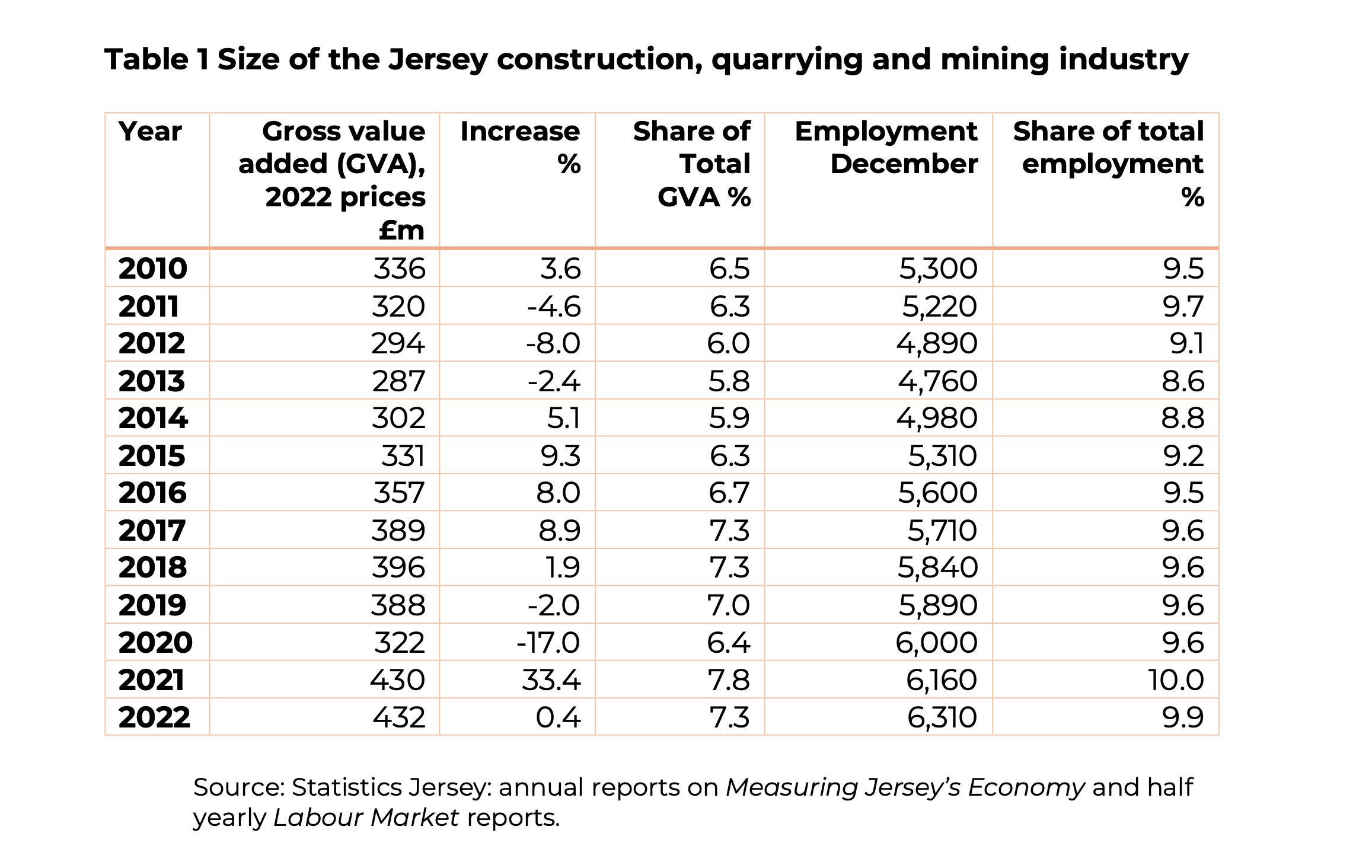

In 2022 the construction, quarrying and mining industry was responsible for £432 million of economic output, measured as gross value added. This accounted for 7.3% of economic activity. The contribution of the industry to total economic activity has fluctuated in a narrow range since 2010, from 5.8% to 7.8%, with generally a slightly upward trend.

The industry employed 6,310 people in December 2022, 9.9% of the total labour force. Again, the figure has fluctuated in a narrow range.

Table 1 shows key statistics for the industry from 2010. It should be noted that the sharp fluctuations in 2020 and 2021 were a consequence of the pandemic.

The annual Measuring Jersey’s Economy reports show gross value added per full time employee. In December 2022 the figure for construction, quarrying and mining was £68,000, lower than the average for the economy as a whole of £84,000, a figure heavily weighted by the exceptionally high figure for finance of £208,000. For comparison, the figure for wholesale and retail was £55,000, for public administration £62,000 and for hospitality £42,000.

The 2021 Census gave a breakdown of workers by place of birth. 39% of workers in the construction and quarrying sector were born in Jersey, almost the same as the overall proportion for the Island of 40%. The main significant variation from the overall position was that 18% of workers were born in Portugal/Madeira compared with 12% of all workers. Conversely, 2% were born outside Europe compared with 7% for the whole workforce.

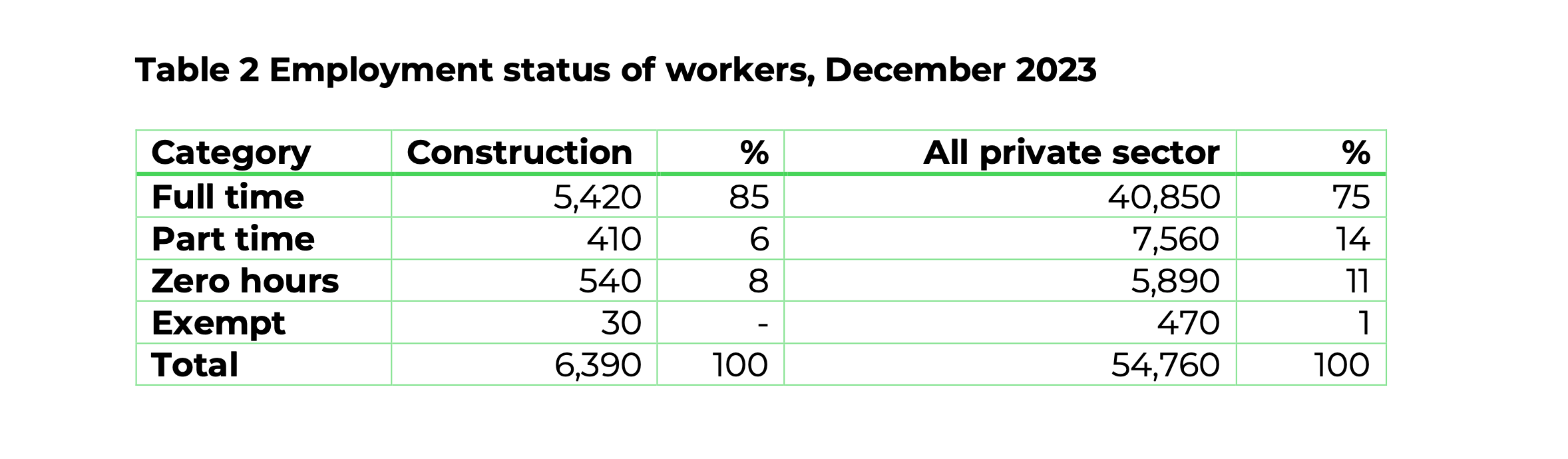

The December 2023 Labour Market report gives a breakdown of jobs by employment status. Table 2 shows the data.

The table shows that 85% of workers in construction were employed full time, compared with 75% in the private sector as a whole. Part-time and zero hours workers were significantly lower. It should be noted that the nature of construction is that there is significant casual labour which may well be recorded as full time if only for short periods.

Notwithstanding strict immigration controls it is relatively easy for off-island contractors and workers to operate in Jersey. For five days’ work in a year no licence is required. For longer periods licences cost £592 for up to 30 days increasing to £4,144 for a one-year licence. It is probably also the case that some UK businesses and workers operate in Jersey on an informal basis without a licence. Both licensed and informal activity may well be extensive, but cannot be measured and in any event would not be classed as part of Jersey’s construction industry.

The construction industry in Jersey – comparative data

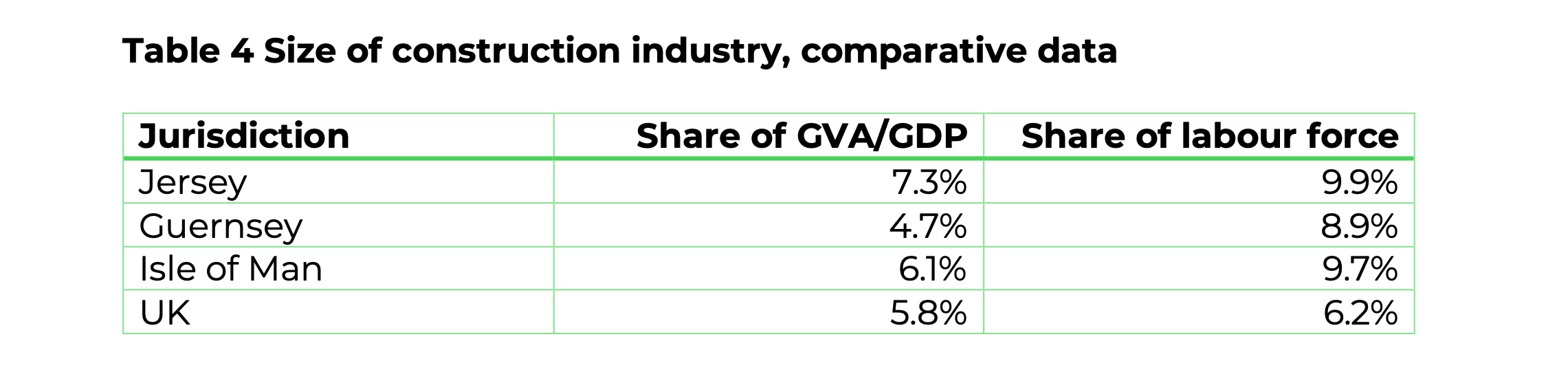

The Guernsey Annual GVA and GDP Bulletin, published in December 2023, reported that in 2022 the GVA of the construction industry was £158 million, out of total GVA of £3,348 million. Construction accounted for 4.7% of total GVA, significantly less than the Jersey figure of 7.3%. The share of GVA has increased steadily from 3.7% in 2017. Construction has been the second faster growing sector of the economy, utilities being the fastest growing. Guernsey’s electronic census report for December 2023 reported that 2,969 workers were employed in construction, 8.9% of the total labour force.

The Isle of Man National Income Report 2021/22 (published in March 2024) showed that construction accounted for £328 million out of national income of £5,347 million, 6.1% of the total. The only employment figures are from the 2021 census. This recorded 4,214 people in construction, 9.7% of the total.

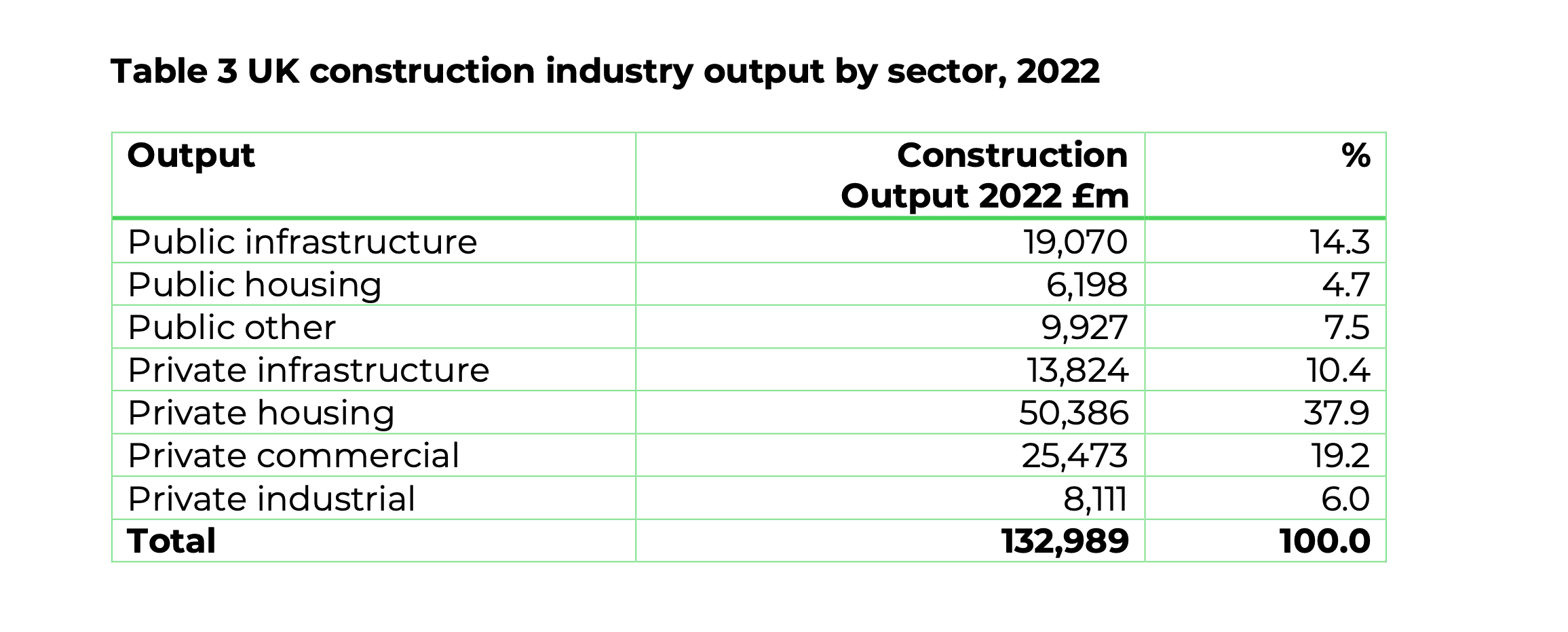

In the UK in 2023 the construction industry output was £133 billion 5.8% of GDP of £2,274 billion. Construction output has been on a steadily rising trend, from £75 billion in 2010 to £133 billion in 2022. In January-March 2024 the construction industry employed 2,079,000 people, 6.3% of the total labour force of 32,977,000.

The Office for National Statistics publishes a breakdown of construction activity between the main categories. Table 3 shows the data.

Table 4 summarises the comparative data. Not too much significanceshould be read into the differences because of slightly differing definitions and time periods. However, as a general conclusion the construction industry in Jersey is a larger component of economic activity than it is in Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK.

The market for construction in Jersey

The market for construction in Jersey comprise five large developers, a significant number of small commercial developers and thousands of homeowners.

The five large developers are –

- The Government of Jersey for major projects including the new hospital, sewage works, schools and leisure facilities and also significant repair and maintenance work. The current Government Plan includes the following relevant to construction work –

o In 2024 capital expenditure on estates is estimated at £46 million, on infrastructure £30 million and on the schools estate £11 million.

o In 2024 £19 million is allocated to continual improvements – roads, sea defences, drains etc.

o Expenditure on new healthcare facilities is estimated at £70 million in 2024, increasing steadily to £314 million in 2027.

- Andium Homes, the Government’s social housing provider, which in 2022 spent £88 million on new housing and £17 million on improvements and repairs to existing properties.

- The Jersey Development Company, owned by the Government, which undertakes both residential and office development. It completed the large Horizon residential development in 2024 and currently has no projects under construction.

- Dandara, a privately owned company, which also operates in the Isle of Man and Great Britain. As a developer, Dandara’s primary focus is the housing market.

- Le Masurier, a privately owned company, is Jersey-based but operates throughout the UK and which undertake all types of major development.

The largest category of clients are thousands of property owners for improvements, repairs, renovations and maintenance work. The Jersey Household Spending report 2021/22 showed that households spent an average of £1.70 a week on materials for repairs and maintenance, £5.90 a week on services for repairs and maintenance and £56.80 on capital improvements to main home. The final two categories count as construction and equate to annual expenditure of £14 million for services for repairs and maintenance and £132 million for capital improvements. The figure for services for repairs and maintenance is considerably lower than the equivalent UK figure (£5.90 as against £8.20) while that for capital expenditure is considerably higher (£56.80 as against £30.10). The capital expenditure figure must be viewed with caution because of the small sample size. However, it is consistent with the figure in the previous survey, for 2014/15, of £40.20. Taken at face value the £56.80 figure suggests that one third of construction demand is in this category. Expenditure by home owners on improvements may also explain why the construction industry in Jersey is a much larger component of economic activity than it is in the UK.

Other significant clients are smaller housing and commercial developers, typically undertaking one project at a time.

Structure of the construction industry in Jersey

As in other jurisdictions the construction industry is characterised by a large number of small companies and a small number of large companies. The industry ranges from larger construction companies undertaking only major projects to one-person businesses undertaking activities such as tiling or plastering. There are many submarkets with most companies operating in just a few.

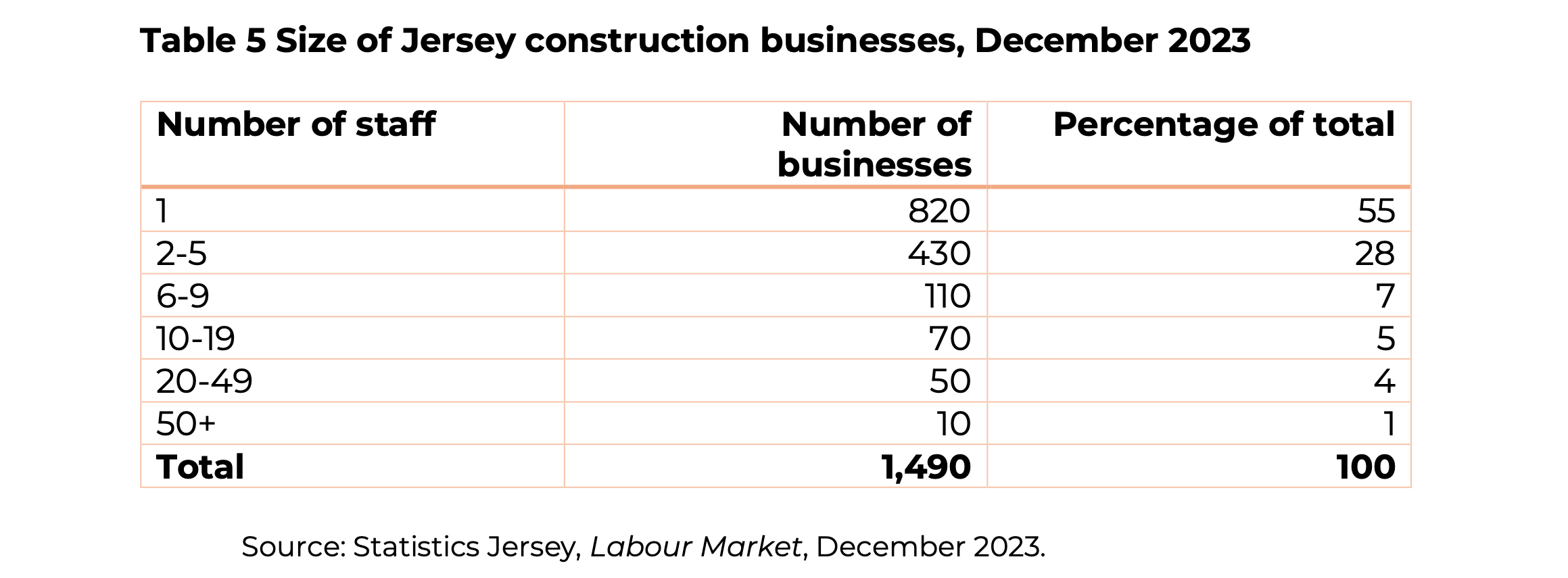

The only published breakdown of the industry is by number of workers. Table 5 shows the data.

It will be seen that there were 1,490 companies, but 55% comprised one person and a further 28% comprised between two and five staff. Just 10 companies had 50 or more staff. In the UK 57% of construction businesses have just one person, although a further 12% are classed as sole proprietors with no staff.

The largest contractors at present are –

- Dandara for its own developments but also for other commercial clients. Dandara makes extensive use of its own employed staff.

- Rok, which makes extensive use of subcontractors.

- Legendre, the 10 th largest company in France, which built the Horizon development with the Jersey Development Company and which is understood to be interested in further projects.

In 2023, the then largest contractor, Camerons, collapsed. It cited spiralling material and labour costs, strains in the supply chain and problematic contracts as well as the impact of the pandemic and Brexit, as the reasons for folding. It was at the time working on two major projects. On a housing project, the developer, Andium, commissioned Rok to complete the project. On a mixed-use project, the developer, Le Masurier, appointed Gardiner & Theobald, a project management company, to handle the project. As is common in such arrangements many of the subcontractors and workers previously employed continued working on the project but for different employers. When the contractor on the sewage treatment plant collapsed in 2021 the client, the Jersey Government, took on the role directly.

There are a number of smaller general contractors including Hacqouil and Cook, Ashbe, Mitchell Building Contractors, Style Group, Coutanche Construction and the Mac group.

In addition to general contractors there is a significant number of companies working in specialist areas such as demolition, scaffolding, groundworks, mechanical and electrical engineering, glazing and landscaping.

Other companies include small housebuilders, which may also be developers, maintenance and repairs contractors, renovation and improvement specialists and companies specialising in home improvements. Major companies in the home improvement market include Hydropool (pools, hot tubs, outdoor kitchens and garden rooms), Beaumont Home Centre (kitchens, bathrooms and bedrooms), Pallot Glass and Windows (conservatories, windows and doors) and Platinum Pools and Spas (swimming pools and hot tubs).

Construction needs different equipment at different times of a project. It would not be economical for contractors to hold equipment that they rarely use so they hire equipment and operators from specialist companies. Scaffolding, cranes, earth moving equipment and concrete mixers are sourced in this way. SGB Hire is the major supplier of equipment available on a short-term or long-term hire basis.

Construction requires materials ranging from raw materials such as sand to bathrooms and kitchens, which can be delivered on-site largely completed. There are two major raw material providers in the island –

- Ronez supplies aggregates, ready-mixed concrete, asphalt and precast concrete products. It operates from the St John’s Quarry. It also operates in Guernsey.

- Granite Products, part of wider Brett Group, operates a granite quarry and manufactures and supplies ready-mixed concrete, aggregates and concrete.

Two companies, Jersey Monumental Company and Le Pelley, specialise in stone surfaces.

Contractors aim to hold minimum stocks, buying what they need to be delivered when they need it. There are a number of builder supply merchants in Jersey, Normans is the leading builder’s merchant covering every aspect of supply for construction of commercial and home building projects. Since March 2023 it has been part of the Europe-wide STARK Group. It operates from two sites: Commercial Buildings and Five Oaks. The other major builders’ merchants are Pentagon, Jersey Building Supplies and Quantum Building Supplies. The builders’ merchants may also provide some installation services. For very big projects the contractor may source some materials directly from off-island suppliers.

In addition to the companies directly involved in physical construction are the professional service firms including architects, civil engineers, project managers and the many different categories of surveyors.

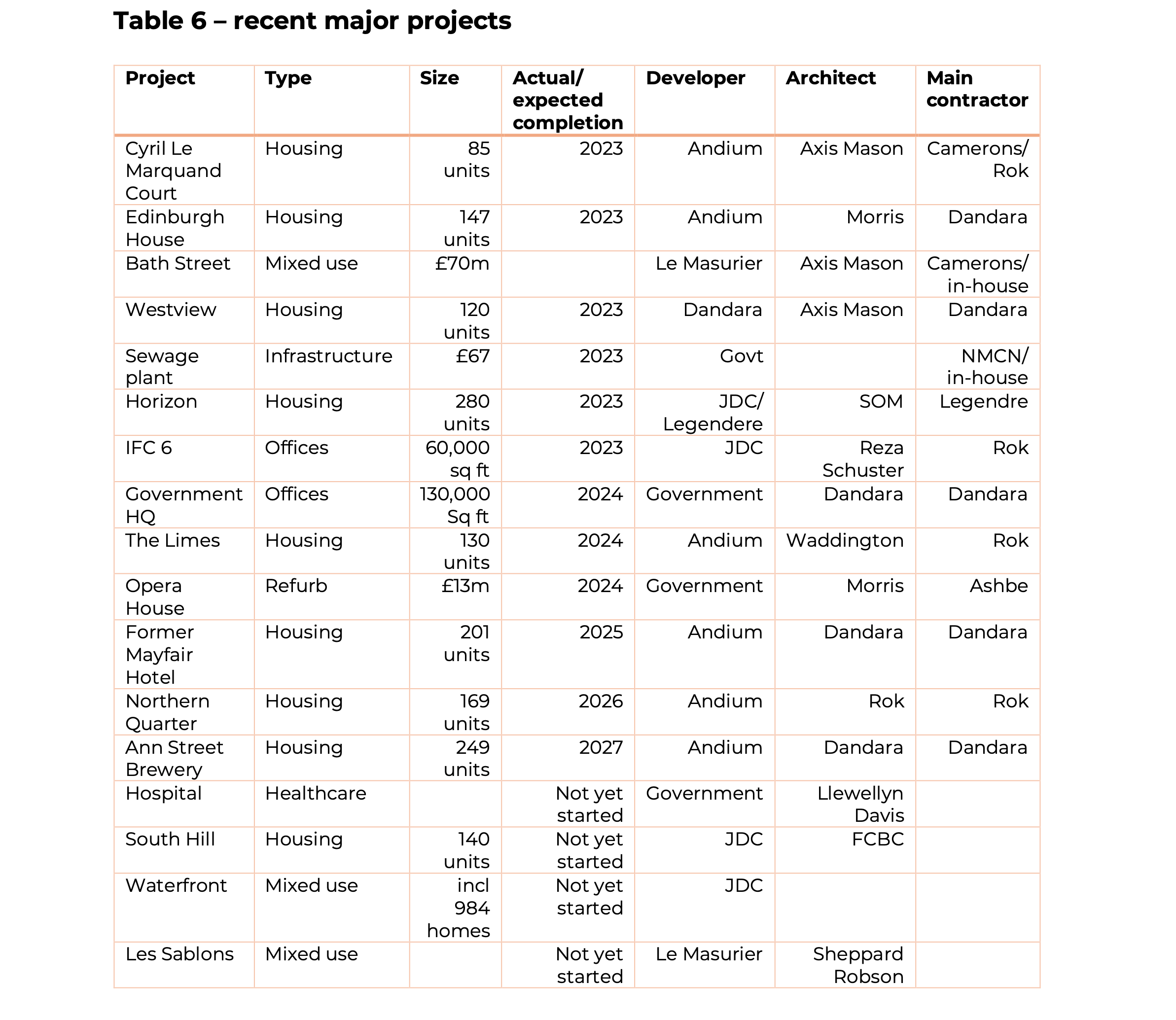

Table 6 list some recent major projects showing the developer, architect and main contractor. The small number of main contractors will be noted.

The value chain

In 2022 the construction industry accounted for £432 million of economic activity, 7.3% of the total economy. The data does not exist to enable this to be disaggregated with any degree of accuracy, nor is it possible to measure how much spend by public bodies, which do publish data on capital programmes, goes off-island. Also, work by architects, surveyors, law firms, accountants and marketing firms is recorded as part of the business services sector, not the construction sector. It is inherent in the way that GVA figures are calculated that, for example, an in-house project manager is recorded as being in the construction sector whereas a project manager doing exactly the same job but retained though a company providing project management services, is recorded as being in the business services sector.

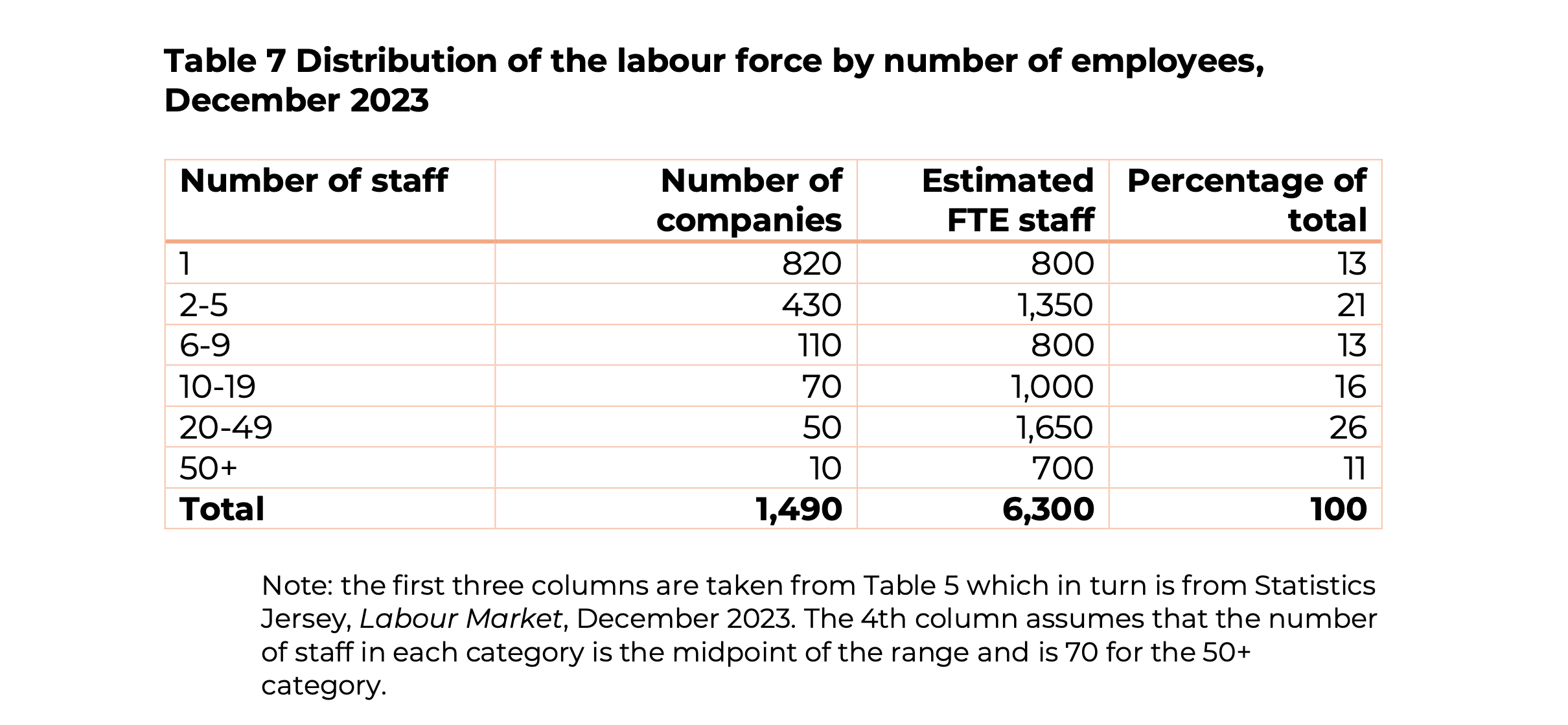

A starting point is to attempt to estimate how the total GVA is distributed between the many businesses. There is no data on this. However, it is possible to estimate how the labour force is distributed. Table 7 shows the data.

The table shows that nearly half of the workforce is employed by companies with fewer than 10 staff and just 11% are employed by companies with 50 or more staff. This cannot be equated precisely with output but is nevertheless indicative. UK data is also relevant. 83% of the total number of employees are in the smallest size band of firm, that is annual turnover under £500,000.

So generally the industry is fragmented with many businesses, but in any sub-sector there may be only a few businesses. For example, at present there are only two on-island contractors capable of handling a very large project and one of those is also a developer and therefore would not be retained by other developers.

It is possible to make broadbrush estimates of how the total volume of activity is divided between various categories over a period of years –

- 25-30% is capital improvements to main homes, several thousand such projects being undertaken each year. Major improvements include new kitchens and bathrooms, extensions, double glazing, outdoor kitchens and hot tubs. Almost all this work is done by local contractors, many very small.

- 15-20% is social housing construction, but subject to significant year-to-year fluctuations given that most social housing is in large schemes. Dandara and Rok are the major contractors in this section of the market.

- 15-20% is private housing by the major developers, Dandara and the Jersey Development Company, and a number of smaller developers. Again, the amount of work fluctuates considerably from year-to-year depending on the state of the market. Some units completed in 2023 or even earlier are still on the market and new construction is likely to be lower in 2024. Dandara is the major contractor. Legendere was the contractor for the 280-unit Horizon scheme but is not currently undertaking any work in the island. A significant number of small contractors are in this market most producing under ten units a year.

- 15-20% is commercial development, mainly offices but also shops and warehouses. This sector show significant fluctuations. Rok and Dandara are the main contractors. For large projects, developers are willing to go off-island for the main contractor.

- 10%-30% of total activity is on infrastructure and health and education facilities. The current Government Plan provides for spending on infrastructure in 2024 of £30 million and on the schools estate of £11 million. Expenditure on new healthcare facilities is estimated at £70 million in 2024, increasing steadily to £314 million in 2027. However, not all that expenditure will count as construction. Some such construction, particularly the new hospital, may be handled by off-Island contractors.

- About 10-15% of total activity is maintenance and repairs by property owners.

The vast majority of all construction work is handled on-island by local firms. Off-island contractors are most likely to be employed for major contracts or highly specialised services. However, the market economy is such that UK contractors and individual workers are able to operate in Jersey with little difficulty and both help fill gaps in the supply chain and exert competitive pressure on local companies.

That the Jersey construction market is to a significant extent integrated into the UK market enables supply to react quickly to demand. It has already been noted that the Jersey Development Company for its Horizon residential development engaged a large French company, Legendre, as a joint venture partner, that company undertaking the construction work. More generally, in evidence to the Environment, Housing and Infrastructure Scrutiny Panel for its report Affordable housing: supply and delivery (2021) Lee Henry, the Managing Director of the Jersey Development Company, said that for the first two buildings in the International Finance Centre –

the entire superstructure and envelope of those buildings were provided by off-Island subcontractors. They are present on the Island for the period within which their work package is on site and then they depart. That has been a way to, as I say, increase the capacity of the Island and has been successfully deployed on previous deliveries.

And when the Horizon project fell behind schedule as a result of supply chain problems and significant labour shortages its joint venture partner Groupe Legendre secured additional labour from outside the island to minimise further delays.

More generally Lee Henry said –

On the delivery side, a number of the projects that we have been involved in, and that other developers and contractors have been involved in, do rely upon off-Island subcontractors, not only to supplement the local capacity but also there may be specialist elements to the builds that require an off-Island specialist subcontractor to be parachuted in.

This view was endorsed by the Housing Policy Development Board in its 2020 report –

The construction market in Jersey was seen by stakeholders as being relatively self-sustaining at projected supply levels with opportunities to access local labour (as well as train local labour such as through partnerships created by the Jersey Construction Council (JCC) with Highlands College) and also the ability to access both UK and French supply chains (for example the use of a French contractor, Groupe Legendre for the Horizon JDC scheme at St Helier Waterfront) in the event of large development projects.

Special Jersey factors affecting the construction market

There are several factors that differentiate the construction market in Jersey from that in most other jurisdictions.

Jersey is a small Island. Freight costs are inevitably higher because a ferry crossing has to be added to transport costs in the UK, from where most building materials are sourced. Labour costs are also high. The small size of the market means that there is less scope to take advantage of economies of scale. The consultancy, Arcadis, produces an International Cost Construction Index. In its 2024 index London was the highest cost city. Anecdotal evidence suggests that construction costs in Jersey are 10% higher than in London. However, a 2019 report, Development in Jersey , for the Housing Policy Development Board by the consultants Altair suggested that the cost of building in Jersey was marginally lower than in London. The report commented: “Despite general anecdotal belief

across housing related stakeholders in Jersey, some of the main developers on the island do not see build cost as a significant barrier to their own delivery particularly if delivering large sites for private sale where they employ direct labour”. This analysis is now slightly dated. It may well be that the rise in freight costs has changed the position since 2019.

The Groceries Market Study by Frontier Economics for the JCRA in 2023 observed that the cost of a shopping basket at the same retailer was 12% lower in the UK than in Jersey, made up of 7% for distribution costs, 5% for labour costs and 2% for tax differences. A similar breakdown for construction costs seems reasonable, although given that building materials are bulkier and heavier than food the effect may be greater.

Jersey is a separate legal jurisdiction with different labour, health and safety and other laws and a different tax system. These add costs for off-island providers of goods or services.

The operation of the Jersey planning system.Jersey’s planning system has created challenges for the construction sector. This was illustrated in the Government commissioned report by Jim McKinnon CBE, former Chief Planner to the Scottish Government. The Review of Planning for the Government of Jersey was published in May 2023. Issues he identified in that report and in a follow up report a year later included a deficient IT system, targets not being met, the difficulty of contacting planners, the process for validating and registering applications being totally unfit for purpose and the Planning Committee being increasingly likely to refuse applications and less likely to take a decision in accordance with planning officials' advice.

In its 2022 Annual Report the Jersey Development Company commented -

Planning refusal on our proposed redevelopment of South Hill [to create apartments]came as a surprise to us, as we had worked closely with the Planning Department and the Jersey Architects Commission to ensure the design was in line with policy as well as offering an exemplar sustainable development for the island.

The decision of the Assistant Planning Minister in 2023 to overturn an Inspector’s decision on the Les Sablons development (a major project in the town centre including 238 homes, a 103-bedroom hotel, offices, retail and open space) was a good example of a planning decision frustrating a development. The developer appealed the decision to the Royal Court (Jersey’s equivalent of both a crown court and the High Court). The Government decided not to contest the appeal. Accordingly the Court declared the refusal unlawful, and overturned the Minister’s decision on the basis that she had ignored the advice of the planning inspector. However, the initial refusal considerably delayed the project to the extent that the developer said had the viability of the project was questionable.

D2 Real Estate commented on this issue in a blog in October 2023 -

Construction projects require precise coordination of professional teams, manpower, materials, and equipment. Delays in planning disrupt this delicate balance, leading to inefficient resource allocation. Idle workers, unused materials, and underutilised equipment not only contribute to financial losses but can also lead to reduced productivity among the workforces. The knock-on impact to small local sub-contractors cannot be understated. ult to replace.

And

Delays in the planning process, or lack of understanding when Ministers deviate from Planning Inspectors recommendations, can severely undermine the confidence of developers and contractors. Anecdotally we are aware of a number of large developers who are reluctant to invest in large scale development projects in Jersey given the current perception of Planning risk.

These issues are not confined to Jersey. The CMA Market Study of Housebuilding (2024) included the following –

A prior condition for building houses is having permission to build them. We have found that the planning system is exerting a significant downward pressure on the overall number of planning permissions being granted across Great Britain. Over the long-term, the number of permissions being given has been insufficient to support housebuilding at the level required to meet government targets and measures of assessed need.

In particular, we have seen evidence of three key concerns with the planning systems which we consider are limiting its ability to support the level of housebuilding that policymakers believe is needed:

(a) Lack of predictability;

(b) Length, cost, and complexity of the planning process; and

(c) Insufficient clarity, consistency and strength of LPA targets, objectives, and incentives to meet housing need.

We have also seen evidence that problems in the planning systems may be having a disproportionate impact on SME housebuilders.

The CMA’s comments on issues facing small builders are probably as relevant to Jersey as they are to the UK –

SME housebuilders face higher costs, in per-plot terms, than larger competitors when they take a site through planning, because of the size of the sites they develop. Our analysis shows that per-plot direct costs (mainly LA planning fees and consultancy costs) for sites of fewer than 50 plots are around £3,500 on average, compared with £1,500 for sites with 100-500 plots and under £1,000 for more than 500 plots. Given SME housebuilders will naturally tend to seek smaller sites, this indicates the disproportionate financial burden placed on them by the planning system.

The Government is unpredictable in respect of its own developments , the hospital being an obvious example. The Fiscal Policy Panel, in its November 2023 report, referred back to its report a year earlier –

The Panel also recommended that capital projects should go ahead as planned, however, greater certainty in the capital spending pipeline will benefit the wider economy, in particular, the construction sector. The Panel looks forward to the publication of 25-year capital investment outlook in 2024.

The Panel also commented that: “greater certainty of the scale and a pipeline of construction projects should benefit the construction sector”.

The Government is equally unpredictable in respect of releasing land to private developers.

These four factors add considerable friction, and therefore costs, to the whole development process and to the construction part of it specifically.

It is understood that the Government is planning a construction activity database which would aim to help all those involved in the process to plan more effectively. However, there is no secrecy about major developments and it is assumed that the major industry participants are already well aware of when major developments are likely to come onstream.

Industry views

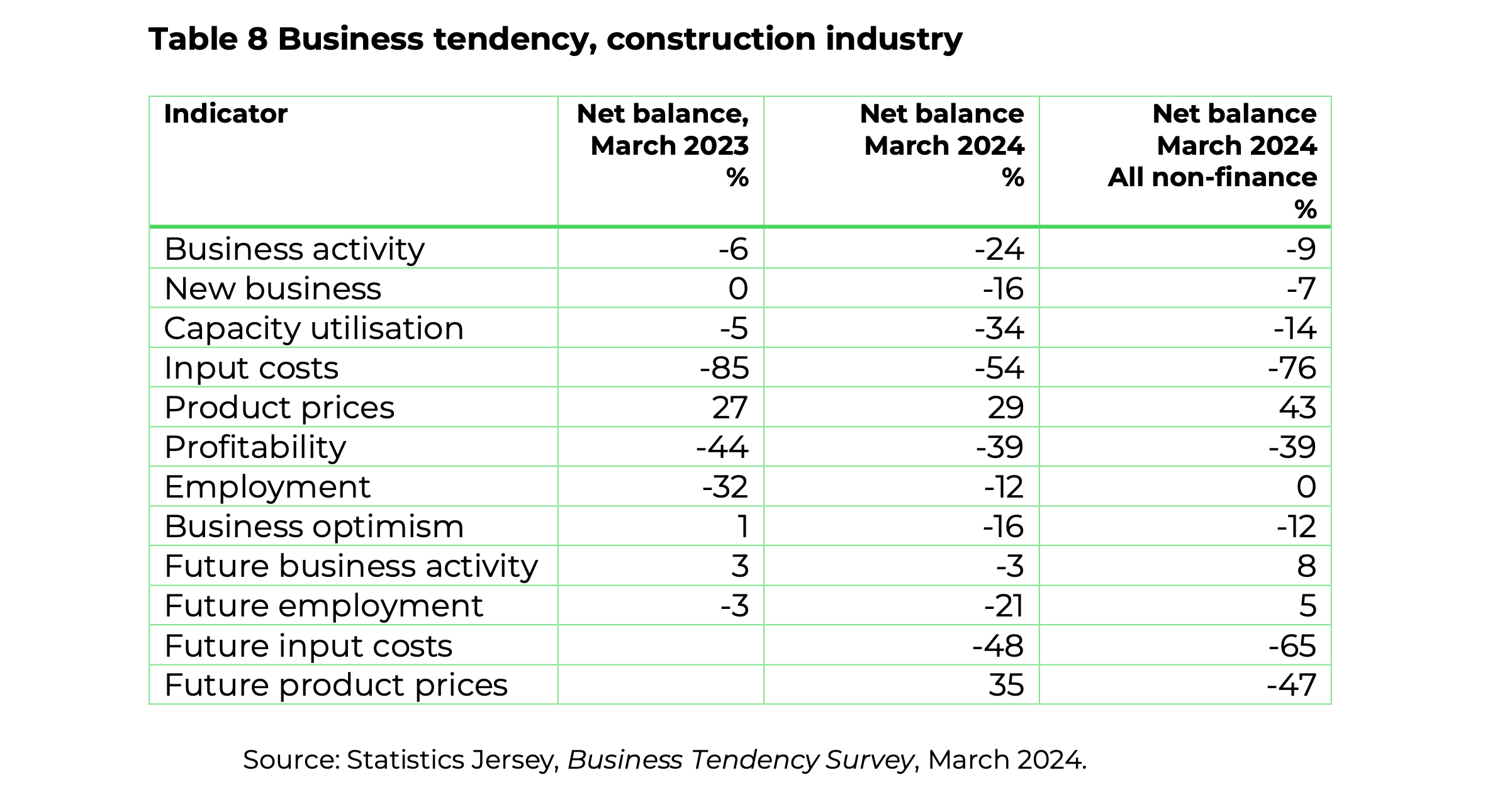

The Business Tendency Survey published by Statistics Jersey gives useful data on attitudes of businesses on key variables. Table 8 shows the figures for the “net balance” (that is positive views minus negative views) for the construction sector and the whole of the non-finance part of the economy.

A few points merit noting –

- The figures for construction are broadly similar to those for the whole of the non-finance sector.

- Input costs have consistently shown a high negative net balance, over 90% for the whole of 2022, falling to the still high level of 54% in March 2024.

- Capacity utilisation in March 2024 showed the highest net negative balance since 2019, other than in June 2020 at a time of maximum lockdown. (Capacity utilisation is defined as current business activity relative to normal capacity. A negative figure indicates that current business activity is below normal capacity.)

Jersey’s Fiscal Policy Panel publishes an annual report which analyses economic developments. In its November 2023 report it included a specific comment on the construction sector –

The construction sector did not grow in 2022. Further, the sector saw the collapse of two construction companies in 2023 because of firm-specific reasons. The sector has been buffeted by rising costs of materials and a slowdown in the housing market. The sector expressed concern about the future pipeline of work as a result of changes to the plans for the New Healthcare Facilities and delays in the planning process for a number of proposed developments.

It is helpful to expand on this point. It was noted at the beginning of this paper that the whole of the development activity is lumpy. The ideal would be a steady flow of projects coming on-stream so that main contractors and specialists such as architects, demolition contractors, lift installers, utility providers and equipment hire companies could move smoothly with their workers from one project to another. But the nature of the industry is such that this does not happen. Planned projects, such as the hospital and Les Sablons, can be delayed for political or planning reasons, which accentuates the natural lumpiness.

This is well illustrated in the Business Tendency surveys. For construction, the net balance in respect of capacity utilisation deteriorated from +20% in March 2022 to -5% in March 2023 and -34% in March 2024. This 54% swing compares with a 23% swing for the whole of non-finance sector. No significant new projects are due to commence in 2024, and it is understood that some contractors are laying off workers as a result.