Policy Brief

Primary and secondary education

Introduction

Jersey has a complex structure of schools comprising fully independent schools with no government funding, private schools with government funding, fee-paying government schools, and non-fee-paying government schools.

Key policy issues are the implications of the significant decline in the number of children, the structure and inclusiveness of secondary education, and attainment levels. This brief describes the structure of the primary and secondary education system and analyses the key policy issues.

Summary

Education in Jersey is governed by the Education (Jersey) Law 1999 through the Children Young People, Education Skills (CYPES) Department. There is a specific Jersey Curriculum, based on the National Curriculum for England.

There are 22 non-fee-paying state primary schools, two fee-paying state primary schools, and six fee-paying private primary schools. The five non-fee-paying state schools in St Helier have an average of 317 students, while the seven parishes with one school only have between 149 and 380 students.

There are six separate categories of secondary school, including four non-fee-paying schools covering the 11-16 age group, four fee-paying schools with state support, and Hautlieu, a non-fee-paying school which covers the 14-18 age range.

There has been a sharp decline in births from 1,008 in 2016 to 716 in 2024. This has already fed through to the numbers in reception classes of primary schools – from 1,066 in 2020/21 to 841 in 2024/25. There has also been a move away from private schools to state schools, including those that are fee-paying.

Primary and secondary education have not been priorities for the current Council of Ministers.

The government publishes very little data on attainment levels for either primary or secondary education and cautions against any comparisons.

For primary schools in 2023/24, at Year 6, 75% of pupils were considered to be “secure” in reading, 61% in writing, and 64% in mathematics.

At secondary level, attainment seem on a par with England as a whole, but substantially worse than the best performing parts of England.

The education system in Jersey is not inclusive, a point made in a number of external reports. A November 2025 report concluded: “Overall, the current leadership, organisation, systems, strategies, oversight and accountability arrangements, in relation to inclusive education in Jersey are not sufficiently effective. Consequently, there is too great an inconsistency in the experiences and outcomes for Jersey’s children and young people with SEND.”

The funding formula for schools was significantly reformed in 2020. However, collectively, schools have run significant deficits. The main reasons cited for this are staff funding pressure and the costs of inclusion.

Legislation and administration

Education in Jersey is governed by the Education (Jersey) Law 1999. The provisions include –

- The compulsory school age, defined as “the period beginning on the first day of the school term in which the child’s fifth birthday falls and ending on 30th June in the school year in which the child attains the age of 16 year”.

- A list of “provided schools”, that is, state schools (including those that are fee-paying).

- Provision for special education needs.

- A duty: “The States shall promote the spiritual, moral, intellectual, cultural, social and physical development of the people of Jersey and, in particular, of the children of Jersey.”

- A responsibility on the Minister “from year to year to –

(a) review the numbers of school places available, both in provided and non-provided schools; and

(b) assess the current and future requirements for provision of school places by reference to the ages and numbers of the children of Jersey.”

- A parental right to choose which provided school a child will attend.

- A responsibility on the Minister to establish the Jersey curriculum.

- Provisions for behaviour and discipline.

- A requirement for the registration of non-provided schools and for the Minister to provide financial support to such schools.

- Provisions for governing bodies including for the Minister to delegate responsibilities to them.

The relevant department is the Department of Children, Young People, Education and Skills.

The Jersey Curriculum is based on the National Curriculum for England, adapted to reflect the Island’s unique heritage and environment, and the needs of the local economy.

Primary schools

The primary schools comprise –

- 22 non-fee-paying state primary schools,

- Two fee-paying state primary schools - Victoria College Preparatory School and Jersey College for Girls Preparatory School, each of which is connected to a secondary school.

- Six fee-paying private schools - St Michael’s, St George’s, Helvetia, FCJ, Beaulieu and De la Salle, the last two are which are connected to secondary schools.

In the 2024/25 academic year, there were 1,113 pupils at private schools and 5,995 at state schools; for the latter, 648 were at fee-paying schools. There has been a significant move of pupils from private schools to state schools. In 2021, 1,406 children attended private schools and 6,648 attended state schools. The private school proportion has therefore decreased from 17% to 15%. However, this is a little misleading as the two fee-paying state schools have more in common with the private schools than with the non-fee-paying state schools. The private schools and fee-paying state schools have a combined share of 25% of the primary student population.

State primary school enrolments are based on the parishes’ catchment areas, resulting in substantial differences in school size across the island.

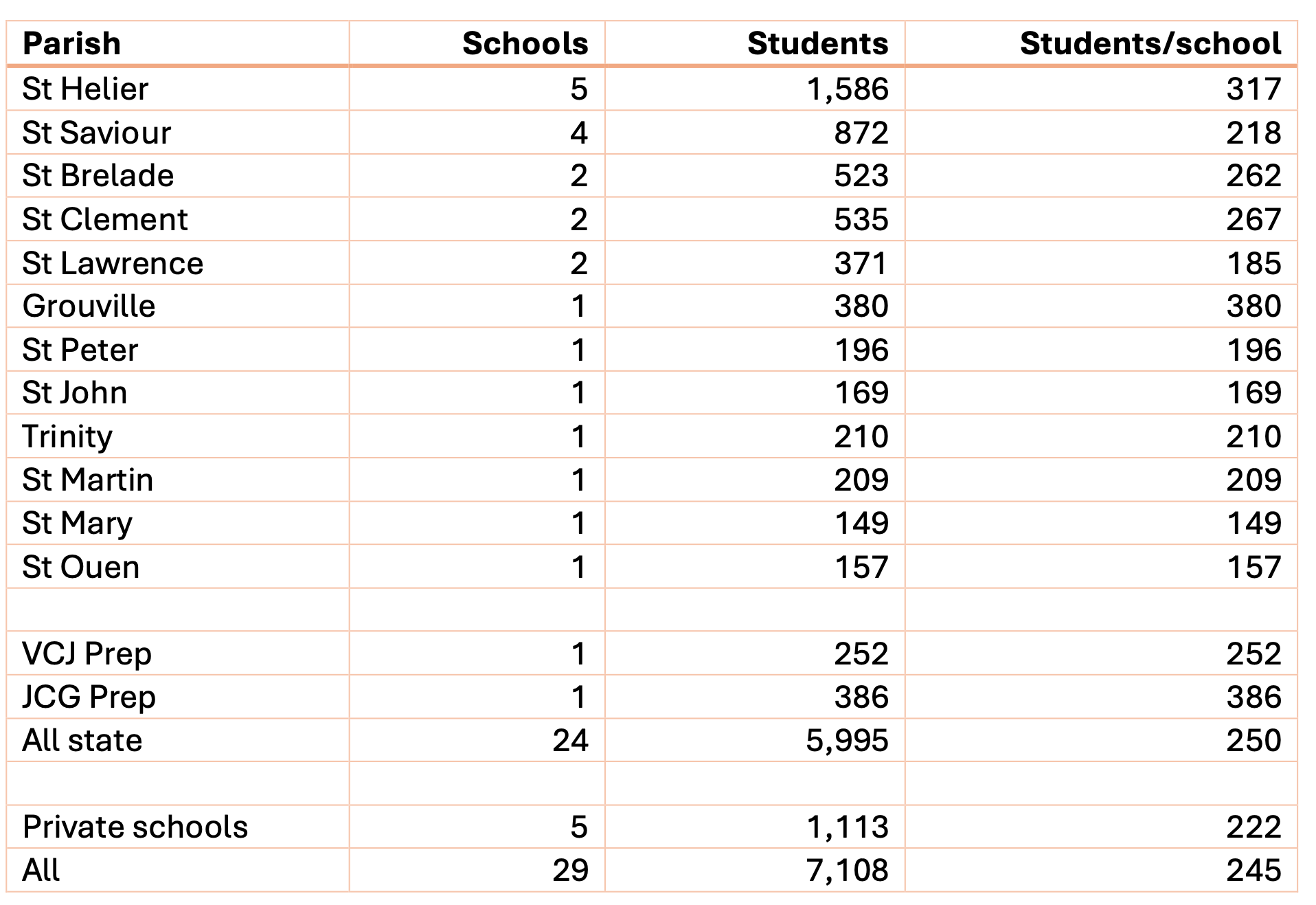

Table 1 shows the key statistics. The figures, other than for the private schools, are taken from a Freedom of Information request dated 16 December 2025.

Table 1 Jersey primary school, Autumn 2025

It will be seen that there is a significant difference between St Helier, where the five non-fee-paying state schools have an average of 317 students, while the seven parishes with one school only have between 149 and 380 students. The smallest primary school, Grands Vaux in St Helier, had 114 pupils; the largest, D’Auvergne in St Helier, had 428.

Secondary schools

The secondary schools fall into six categories –

- Four non-fee-paying state secondary schools (Grainville, Le Rocquier, Haute Vallée and Les Quennevais) which cover the 11-16 age group.

- Hautlieu, a non-fee-paying, selective school, which covers the 14-18 age group.

- Two fee-paying state secondary schools (Victoria College and the Jersey College for Girls).

- Two private secondary schools but with state funding (Beaulieu Convent and De La Salle College).

- St Michael’s School, primarily a prep school but which includes the 11-13 age group.

- Two special schools (La Passerelle and Mont à L’Abbe).

In addition, Highlands College, the island’s only further, higher, and adult college, is state-funded and covers the 16-18 age group (who are not subject to tuition fees).

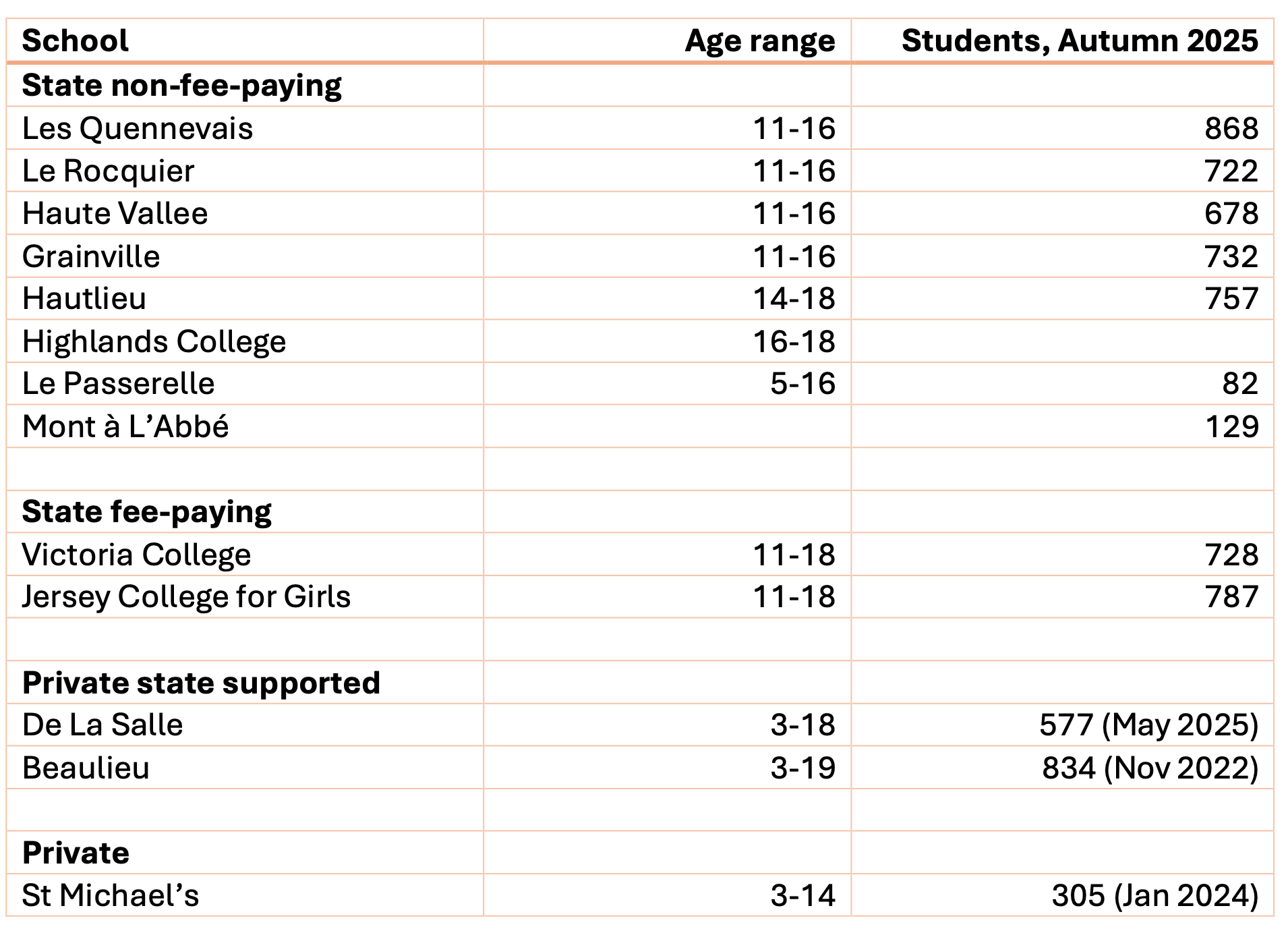

Data on the schools is incomplete. Table 2 shows the best estimates (the definite figures are taken from a Freedom of Information request, dated 16 December 2025).

Table 2 Secondary Schools

Currently, the annual fees for the fee-paying state secondary schools are £8,439 at the Jersey College for Girls and £8,640 at Victoria College. The fees at the private schools are slightly higher - £8,856 at De La Salle and £9,777 at Beaulieu. These are much lower than fees for English public schools. For example, fees charged by the public schools in Dorset are in the £36,000-£41,000 range. This helps to explain the high proportion of secondary school students who are at fee-paying schools – 40% compared with about 8% in England.

Declining student numbers

There has been a sharp decline in births in Jersey in recent years. The number of births peaked at 1,008 in 2016 and has fallen steadily to 716 in 2024. This has already fed through to the numbers in reception classes of primary schools – from 1,066 in 2020/21 to 841 in 2024/25, and a further fall to around 730 within four years.

These trends will, in the fairly near term, require a review of the structure of the primary school sector given that some schools will have very small classes. Longer term, this will feed through to the secondary sector and result in greater competition between schools for students.

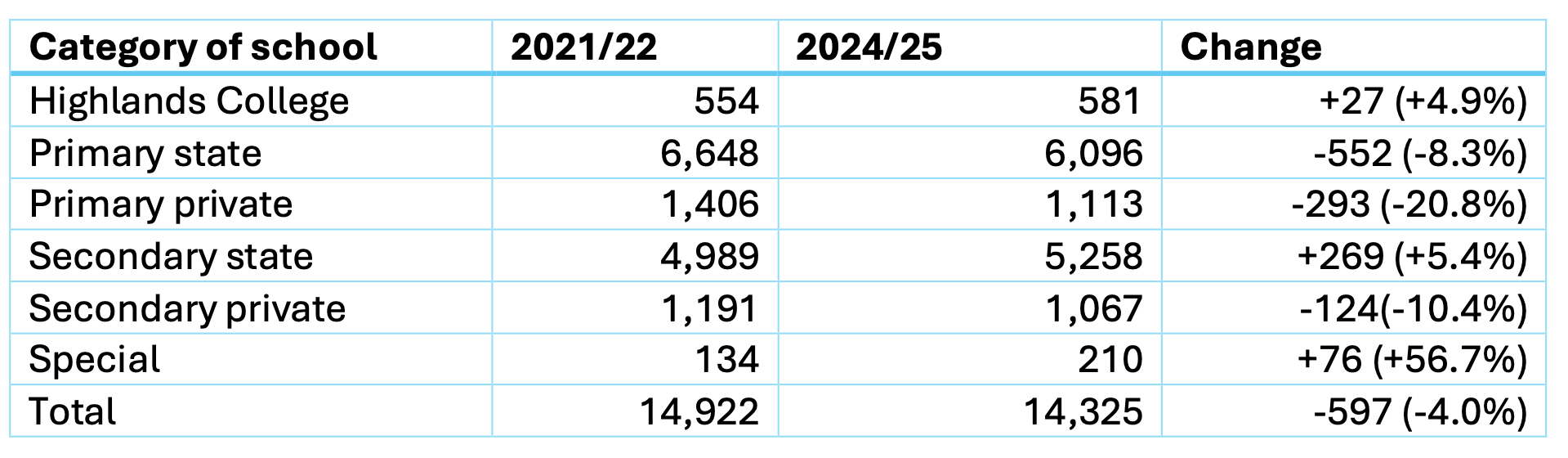

More generally, there has been a move away from private schools to state schools, including those that are fee-paying. Between 2021/22 and 2024/25, the total number of pupils fell by 4%. The numbers attending private schools fell by 16.1% while the numbers attending state schools fell by 2.4%.

Table 3 shows trends in the numbers attending schools.

Table 3 Student numbers 2020/21-2024/25

Source: Schools, pupils and their characteristics.

Policy priorities

In May 2024, the Council of Ministers published its Common Strategic Policy 2024 - 2026. This set out 12 priorities for delivery in the two years. They included three specific to education -

- Extend nursery and childcare provision.

- Provide a nutritious school meal for every child in all States primary schools.

- Increase the provision of lifelong learning and skills development.

The business plans of the Minister of Education for 2024 and for 2025 included nothing specific on primary and secondary education. The issues of the school structure, attainment levels, and inclusive education have not been on the political agenda.

Attainment levels

The page on the Government website of attainment levels is very thin.

The Jersey Schools Review Framework Handbook is the definitive publication. It sets out new benchmarks for standards within Jersey’s schools and explains how the quality assurance system for schools and colleges is implemented.

In each primary school, teacher assessments are made in accordance with a standard framework at the end of Key Stage 1 (year 2) and Key Stage 2 (year 6). Children are assessed as being secure, developing or emerging.

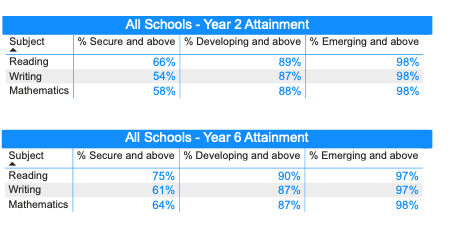

Each state primary school has a website report giving the statistics. This includes a comparison with all schools. Table 4 reproduces the table for all schools.

Table 4 Primary school Year 2 and Year 6 Attainment, 2023/24

The most recent comprehensive report on trends and comparisons between schools is for 2018/19. This showed, for example, that in 2016/17, the Year 2 figures for secure were 61% for reading, 43% for writing, and 59% for mathematics. For Year 6, the figures were 53%, 42%, and 48%.

At GCSE level, the Government publishes headline statistics through press releases. On its a website, it has a single table showing –

- Pupils achieving standard passes (4/C+) in English and Mathematics (71.2% in 2022/23)

- Pupils achieving strong passes (5/B+) in English and Mathematics (49.3% in 2022/23)

The website comments –

Jersey students sit a blend of UK and international GCSEs (IGCSEs), particularly in English and Mathematics. In addition to the use of IGCSEs, Jersey accountability measures take each pupil’s best entry in a subject, whilst England only count their first entry. For these reasons it is not appropriate to directly compare Jersey’s results with those of England.

Similarly, the website cautions against comparisons with earlier years because of the effects of Covid.

The Government does not seek to compare Jersey’s figures with those for England or other jurisdictions. However, in broad terms over the last few years, performance at GCSE and A level has been on a par with England as a whole but significantly below the best performing parts of England, that is London and the South East of England.

The only comparative data on school performance is from the Independent School Funding Review, published in 2020. Among the points it made were –

- Comparing Jersey non-fee-paying schools with their like-for-like equivalents in England shows Jersey non-fee-paying schools underperforming relative to England.

- Further, when you examine “value add” metrics such as Progress 8, non-fee-paying and fee-paying state-maintained schools in Jersey add less value to their pupils’ performance than the equivalent schools in England, while the state-maintained fee-paying schools add significantly above average value – on average adding half a grade per subject to each pupil.

- Comparing the percentage of pupils who left KS4 and went on to take a Level 3 qualification (A-Level or equivalent), Jersey is found to also perform less well than the UK. In 2016, 61.4% of pupils went on to Level 3 study, including pupils who studied for AS levels, compared to 71.2% of pupils in the UK.

In England comprehensive statistics are published for all state schools. The key statistics are -

- Attainment 8 which measures exam results in absolute terms at age 16. There is an equivalent in Jersey - Jersey 8 measure exam results in absolute terms.

- Progress 8 measures value added – that is progress between years 11 and 16.

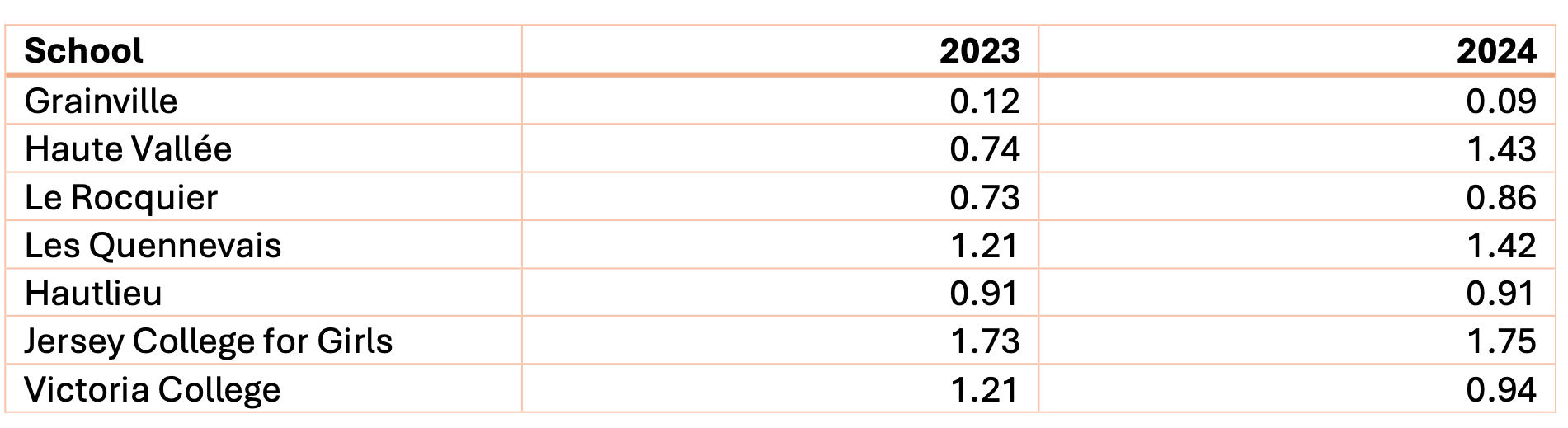

Jersey does not publish Jersey 8 or its equivalent of Progress 8 as a matter of course; rather, it releases data only in response to Freedom of Information requests. Table 5 shows the Jersey value added figures for 2023 and 2024.

Table 5 Jersey 8 Value Added statistics, 2023 and 2024

Not too much should be read into year-to-year variations or small differences between the schools. Any score above 0 indicates that attainment is better than expected. In England, +1.0 means that, on average, pupils at that school achieved one full GCSE grade higher in each of their subjects compared to students with similar starting points nationally. It is not clear how the Jersey figures are calculated, but it is not on the same basis as not all schools can be better than the average.

Inclusive education

In December 2021, the Independent Review of Inclusive Education and early years was published. This reported many elements of good practice and a sound foundation on which to make further progress, but also highlighted some aspects of the education system that are not inclusive. The executive summary of the review stated -

During 2021, the National Association for Special Educational Needs (nasen) undertook an Independent Review Of Inclusive Education And Early Years on behalf of the Government of Jersey (GoJ). Whilst inclusive education can be broad in its interpretation, the focus of this review was on how schools, settings and support services contribute to, or are barriers to, inclusion at a system level. A diverse range of stakeholders were engaged through the review, including children and young people (CYP) and their families.

The evidence-base collated during the review process has led the review team to conclude that whilst there is some exemplary inclusive practice within specific areas of the education system, this is not yet happening consistently because it is not sufficiently reinforced at a strategic, systemic and systematic level. This includes the prioritisation given to realising inclusion, the allocation of resources, and the underpinning policies and processes.

The review team have identified that the prevailing approach to education in Jersey is currently based on separating provision so that it aligns to the needs of different groups of children and young people. Whilst this approach is arguably underpinned by good intentions, it can be a structural barrier to achieving inclusive education.

The review describes a continuum of inclusion that moves forward from segregated provision to partial inclusion to systemic inclusion, and finally to total inclusion.

Having commissioned this review, the GoJ has clearly demonstrated its commitment to developing inclusive education in Jersey. The next step is for the GoJ to apply the inclusion implementation roadmap provided within this report to realise its preferred approach to inclusion. Implementing change of this scale in the Jersey context will inevitably present significant challenges, so it will be important to remember the overriding principle that an inclusive education system benefits not only those who are marginalised, but all children and young people.

The review then listed 50 Recommendations across 23 areas that can support Jersey to move along this continuum of inclusion.

On 16 November 2022, a press release announced that –

A project to develop a vision, charter and framework to make the Island’s education system more inclusive is underway, a year on from a key review.

………..

A key recommendation from the nasen report was that the Island should develop a shared vision of what inclusive education is, and how it can be delivered. It also recommended that any work on inclusion should be co-produced with children, young people, and parents.

The Vision will be supported by a Charter, which will set out the key principles, and which all schools and early years providers will sign up to, and a Practice Framework which will support the development of inclusive practice across the Island.

Over the past 12 months, progress has been made against several of the recommendations made by nasen, including:

- The restructure of La Sente School and merger with La Passerelle to provide a holistic educational service provision for children and young people with Social, Emotional, and Mental Health needs.

- An independent review of mental health provision in schools, which has led to an action plan being developed in partnership with schools.

- £6.1 million proposed in the Government Plan 2023 for inclusion in schools, with a focus on children with special educational needs, and those with a record of need.

- An Additional Resource Centre (ARC) for children with low cognitive ability launched in September at D’Auvergne, with another due to open at Le Rocquier School in 2023.

- Formal training for Special Educational Needs Coordinators has been delivered in collaboration with the University of Winchester.

In October 2025 the Government published the Island SEND Review “an independent external analysis of the current quality of inclusive education provision for Jersey pupils in Government-provided schools with a focus on the quality of provision for pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND)”. The report was by four inspectors, all with relevant experience in England. The summary of its key judgements is set out below –

Overall, the current leadership, organisation, systems, strategies, oversight and accountability arrangements, in relation to inclusive education in Jersey are not sufficiently effective. Consequently, there is too great an inconsistency in the experiences and outcomes for Jersey’s children and young people with SEND.

Pupils with SEND typically reported that they feel comfortable in their schools and most parents reported having a positive relationship with their individual school. However, there are

inconsistencies and a significant number of parents who are concerned about the quality of SEND provision and approaches across Jersey.

The comprehensive National Association for Special Educational Needs (nasen) Review published in 2021 recognised that changing culture takes time, but its recommendations have not yet been

responded to effectively. However, this 2025 review recognises and respects several areas of strong practice, and successful projects, both within the central team and in schools. As a result of these, many schools show a willingness to embrace inclusive education and there are emerging examples of schools collaborating and being creative in meeting the needs of children and young people with SEND.

School funding

The Independent School Funding Review was published in 2020. The Executive summary is set out below.

The Government of Jersey aspires to achieve outstanding educational outcomes for all children. This aspiration is front and centre in the 2020-23 Government Plan and the Independent School Funding Review was commissioned to identify the funding needed to achieve this. This is the final report of the review and recommends what the Government of Jersey needs to do to put children first.

Current funding for non-fee-paying education is low, at £9.2m below the level needed to match high-performing jurisdictions. With this level of funding, children on Jersey achieve academic outcomes broadly in line with England, though disadvantaged children do not currently achieve well. There are also significant mental health and wellbeing challenges for children on Jersey, particularly around anxiety. Overall, there is a significant gap between current provision and the aspiration for a world class education system.

The current low level of funding is most acute for disadvantaged children and those on vocational pathways. In 2019 the school system ran a deficit of £2.4m, and this review has identified that a further £2.8m is needed to properly fund current provision. This would also go some way to closing the gap in spending between students at fee-paying and non-fee-paying government schools, currently standing at £15k across a student’s school career.

This unsustainable financial position is reflected in both the deficits recorded by schools and the quality of provision for children. Within the £2.4m total deficit, all Jersey’s 11-16 schools and many primaries are running deficits, and the rapidly deteriorating position risks a breakdown of financial discipline in the sector if not addressed. Within schools, funding challenges make meeting the needs of the highest-needs children difficult, and this has an impact both on these students and on standards of behaviour across the school system. There is minimal budget headroom in schools for investment in the improvements in teaching and learning that would drive better outcomes.

From this starting point, reaching a world leading education system that puts children first is a journey that will take a number of years. This is also a transformation that goes well beyond funding, as evidence from the world’s top performing education systems shows that once a certain level of investment is reached there is a weak relationship between spending levels and outcomes for students. Jersey already spends above this threshold level. Looking to Finland and other top performing jurisdictions, successful reform requires a deliberate and sequenced policy agenda over at least a decade, with strong alignment of objectives, funding, governance, curriculum and teacher development. This review aims to support Jersey on this journey through:

- Recommending the funding level needed now to stabilise current provision and make the investments in teaching quality and equity to put the system on the path to sustained improvement (an additional £8.5m).

- For the medium-term, identifying the structural changes needed to resolve long standing barriers to effective use of resources in the education system and to improve standards.

- For the long-term, setting up a radically simplified funding formula that has the flexibility to support an evolving policy agenda as the education system develops and improves.

The review then set out immediate, medium term and longer-term priorities.

In December 2024 the Children, Education and Home Affairs Scrutiny Panel published a report Secondary Education Funding . The report includes a comprehensive analysis of school funding and also the structure of the education system. Two of its key findings were –

Between 2018 and 2023 there has been a £9.840 million increase to funding provided by Government to non-fee-paying secondary schools, equating to an increase of 31%. Comparatively, the funding provided by Government towards the provided fee-paying schools has fluctuated slightly but overall it has increased by approximately £676,000, equating to a 13% increase over the same period of time. Comparatively, Jersey’s Retail Price Index (RPI) over the period March 2018 to December 2023 was 33.3%, so Government provided funding has not kept pace with RPI, despite additional funding provided for Education reform.

The financial deficit has decreased for the non-fee paying provided secondary schools since the introduction of the Jersey Funding Formula for Schools (‘funding formula’) (in 2022) but has not been totally removed. The deficit for the fee-paying provided secondary schools has fluctuated over the same period of time (2018-2023), but they are not subject to the new funding formula calculations.

In November 2025 the Comptroller & Auditor General published a report on the Education Reform Programme. It made the following comments on funding –

The primary objective of the ERP school funding formula project was to implement a radically simpler funding formula so all schools and colleges have transparent and equitable budgets and the funding system is flexible for the future. This has been partially achieved.

Following the allocation of £5.5 million of additional funding the schools budget deficit of £3.31 million for 2020 was reduced to a surplus of £240,000 during the first two years of the ERP. Since then, the overall schools’ deficit position has deteriorated year on year. The forecast has ranged from an overspend of £3 million to an overspend of £4.6 million over the first nine months of 2025. The reasons for the largest variances in school spend as reported to the Education Finance Group in June 2025 are staff funding pressure and the costs of inclusion. There are significant issues at the two special schools whose financial position has gone from a deficit of £114,000 at the end of 2022 to a forecast deficit of £2.34 million at the end of 2025.