Research

Early years

Introduction

Life chances are determined to a large extent in the pre-school years. Policy towards early years is therefore critically important, particularly for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. A related issue in Jersey is the impact of the high cost of childcare on working parents. This report analyses these issues and options for Government intervention.

The report draws on three reports for the Government of Jersey: Early Childhood Education and Care: Jersey, 2024 (consultancy, 4Insight); Early Years Roundtable Series 2023/24 and Parents’ and carers’ views on early childhood education and care in Jersey (consultancy, ISOS partnership). It also draws on research in the UK and other jurisdictions, and the discussion at a roundtable convened by the Centre on 13 November 2025.

Summary

The first few years of a child's life provide the foundation for everything that follows. Speech, language and communication skills are particularly important. These develop best through high quality provision in formal settings including nursery classes, nursery schools and playgroups.

Early years support policies are important for maximising the return on public expenditure, helping those from disadvantaged backgrounds and enabling parents to return to work.

The number of births in Jersey has been falling, from 1,008 in 2016 to 716 in 2024. This trend is directly affecting the demand for early years provision and is also creating surplus capacity in primary schools.

Childcare provision is regulated under the Day Care of Children (Jersey) Law, 2002 and the Early Years Statutory Requirements.

Early-years services are provided by state primary schools, private nurseries, regulated child-minders and accredited nannies. Private nurseries cover all age groups; primary schools are significant providers only for the 3–4-year-old age range; while child-minders concentrate in the 0-3 age range. There is also provision outside the formal system.

Childcare costs in Jersey are high. Average fees charged to parents are almost 50% higher than in England as a whole and about 12% higher than in London. Fees charged by child-minders are more than a third higher than in London.

Financial assistance for childcare includes tax allowances, income-support payments and direct support for 3-4 year-olds and, from January 2026, 2-3 year-olds.

The current Council of Ministers has, as one of its strategic policies, "extend nursery and childcare provision". The goal is to move toward a universal offer for 2-3 year-olds, starting with those who have additional needs. The decision to provide 15 hours of support for 2-3 year-olds from the beginning of 2026 will help parents meet the cost of childcare but is unlikely to have a significant impact on the parents’ willingness to return to work.

Jersey’s performance in respect of “school readiness” seems to be below the best-performing local authorities in England, and more than 10% below the level required for a “green” rating under the Department’s own criteria.

Key public policy issues:

- Difficulties in recruiting staff.

- Stability of the funding model.

- Competition between nurseries and primary schools.

- The balance of public expenditure between the different age groups.

- Performance in respect of “school readiness”.

The importance of early years support policies

The first few years of a child's life provide the foundation for everything that follows. Speech, language and communication skills are particularly important. These develop best through high quality provision in formal settings including nursery classes, nursery schools and playgroups.

The importance of early years can be summarised in this quote from the 2023 Ofsted report International Perspectives on Early Years .

International research shows that high-quality early years provision provides long-term benefits for both cognitive and social and emotional skills. Children who spend longer in early years provision have better educational outcomes. International research has also found that high-quality early years provision particularly benefits children from low-income backgrounds. Accessible, affordable, high-quality provision not only supports family income by ensuring that parents can work, but also supports children’s development, well-being and success later in life.

In more detail, policies that support children in their first five years are critical for three main reasons.

Maximum return on public investment

Research by Nobel-laureate economist James Heckman provides strong evidence that investments in early childhood (ages 0-5) yield the highest long-term social and economic returns. His work – often called the Heckman Equation or the Heckman Curve – shows that the rate of return on human-capital investment is greatest for the youngest children. Key findings include -

- Highest Returns on Investment: Heckman's analysis of long-term studies (e.g., the Perry Preschool Project) shows that high-quality, comprehensive early-childhood programmes for disadvantaged children can yield a return of 7-13% per year–higher than investments in later educational stages, job training, or even the stock market.

- Skill Begets Skill: Foundational cognitive and non-cognitive skills -motivation, self-control, perseverance - develop in early childhood. These "soft skills" are crucial for success in school and the workplace and are far more costly to remediate later in life.

- Reduced Societal Costs: Long-term benefits extend beyond the individual:

- Lower crime rates: participants are less likely to be arrested or imprisoned.

- Better health outcomes: Lower incidence of chronic disease as adults.

- Higher educational attainment: Greater likelihood of pursuing higher education

- Increased earnings and productivity: Higher adult incomes, greater tax contributions.

Helping Those from Disadvantaged Backgrounds

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to fall behind their peers, a gap that can be difficult to close later in life. Early years support policies aim to address this by -

- Improving "school readiness": High-quality early education and childcare provide a structured environment where all children develop crucial social, emotional, and cognitive skills before starting primary school. This is particularly beneficial for children from low-income families who may lack such resources at home.

- Breaking the cycle of poverty: Targeted governmental support, such as free or subsidised early years education, helps decouple a child's future prospects from their family background. This offers a more equal footing and can improve educational outcomes later in life.

- Integrated Family Support: Policies often include broader support for families, such as health-visiting services and parenting programmes, ensuring that no family "falls through the net" and that those most in need receive the support they require.

Enabling Parents to Return to Work

High childcare costs are a major barrier for many parents, especially mothers, who typically shoulder a disproportionate share of childcare responsibilities. Reducing these costs can significantly increase female labour-force participation, yielding several economic benefits:

- Boosts Economic Growth: More mothers returning to work, or increasing their working hours, expands the productive workforce.

- Reduces the Gender Wage Gap: The earnings difference between men and women often widens with the birth of the first child. Affordable childcare allows mothers to maintain their careers, progress in their jobs, and prevent this gap from expanding.

- Retains Skilled Workers: Employers retain experienced female employees who might otherwise reduce hours or leave the workforce entirely due to childcare pressures.

The UK Department for Education has sponsored the Study of Early Education and Development (SEED), a major longitudinal study, designed to provide evidence on the effectiveness of early childhood education and care (ECEC) and to identify any short- and longer-term benefits from government investment in this provision. A report Study of Early Education and Development (SEED): Impact Report on Early Education Use and Child Outcomes at Key Stage 2 was published in July 2025. Following is a summary of the key findings –

- Increased hours of ECEC in formal group settings (nursery classes, nursery schools, or playgroups) was associated with a slight improvement in meeting expected standards in reading, writing, and maths (combined) and reading at KS2.

- An additional 10 hours per week in formal group childcare during early years increased the likelihood of achieving the expected standards in reading, writing, and maths (combined) by approximately 3 percentage points.

- The likelihood of achieving the higher standard in reading, writing and maths (combined) also increased slightly with increased hours spent in formal group settings: the odds increase by 2% with each additional hour a week the child attended.

- Increased hours of ECEC in a formal domestic setting (such as from childminders) was positively associated with achieving the expected standard in science at KS2, whilst increased hours in informal settings (such as from relatives, friends, neighbours) was associated with improved attainment in maths.

- Children from financially disadvantaged families show a more pronounced benefit from increased formal group ECEC attendance. For children who joined the SEED study in the most financially disadvantaged 20% of families, each additional hour of formal childcare per week during their early years was associated with a 4.5% increase in the odds of achieving the expected standard in reading, writing and maths (combined). This improvement is around twice as large as for children overall.

- The positive effects of childcare for financially disadvantaged children were also established at KS1 and have persisted throughout primary school. Combined, these findings indicate that early years childcare is likely of particular importance for children from disadvantaged backgrounds in helping them to succeed academically.

- A better Home Learning Environment index score was linked to a slightly higher likelihood of meeting expected standards in reading, writing, and maths (combined) at KS2.

- An authoritative parenting style, characterised by high responsiveness and high levels of psychological control, and clearer parental limit setting was also found to have a positive impact on KS2 attainment.

- Home environment factors, both in early childhood and later in primary school, were also strongly associated with socio-emotional outcomes at KS2 and able to explain a greater share of children’s socio-emotional outcomes than early years childcare experiences.

- In particular, parental psychological distress, a chaotic home life, a more invasive relationship between mother and child (reflecting issues such as the mother feeling in conflict with or annoyed by her child) were all associated with poorer socio-emotional outcomes at KS2. Associations between these elements of the home environment and poorer outcomes was also found at KS1.

A related report Key Stage 2 attainment and lifetime earnings (July 2025) provides estimates of the lifetime earnings return associated with improvements in attainment at Key Stage 2 (KS2), when pupils are aged 10-11. A key finding was that higher KS2 attainment is associated with higher lifetime earnings. The effect was more significant for maths than for English and for girls than boys, suggesting that increasing overall KS2 attainment could reduce the gender wage gap.

Declining number of under 5s

There has been a sharp decline in births in Jersey in recent years. This directly reduces demand for early years provision and creates surplus capacity in primary schools.

The number of births peaked at 1,008 in 2016 and has fallen steadily to 716 in 2024. This feeds through to the number of pre-school children. There is not an exact relationship because of immigration and emigration but the evidence suggests that this impact is small. Table 1 shows key data.

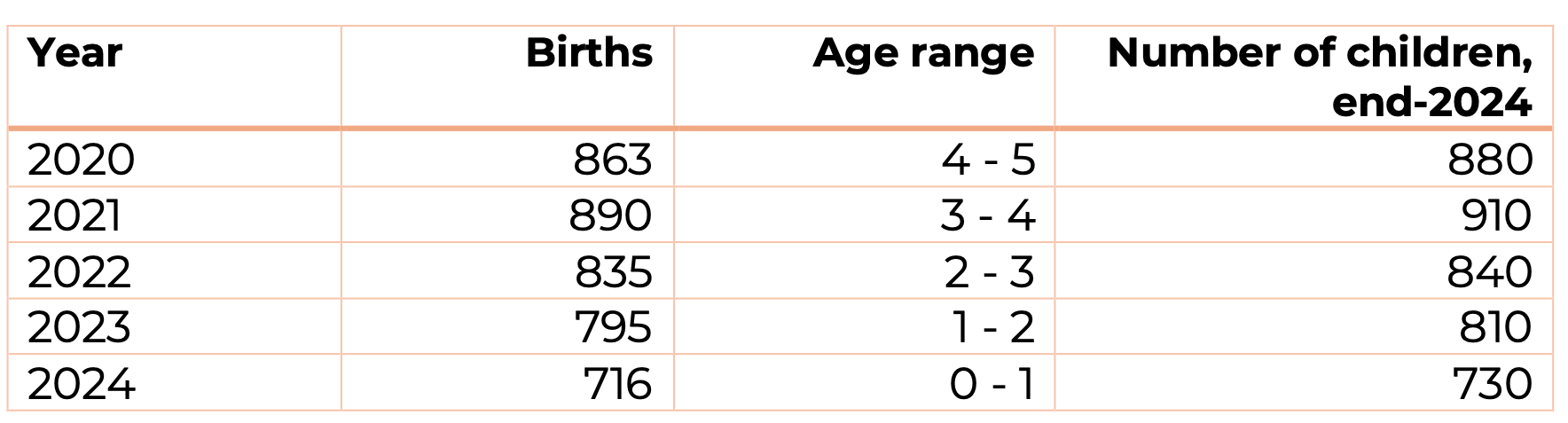

Table 1 Births in Jersey, 2020-2024 and number of children in each age group, end 2024

Sources: Birth figures are taken from the Superintendent Registrar annual statements. Figures for the number of children at the end of 2024 are taken from the Statistics Jersey report Population and migration, December 2024.

There is a good correlation between births in one year and the number of children in each age band in subsequent years.

The 20% fall in the number of births since 2021 is already significantly affecting demand for early years provision and the number of children in reception year classes at state primary schools. Table 2 shows the data.

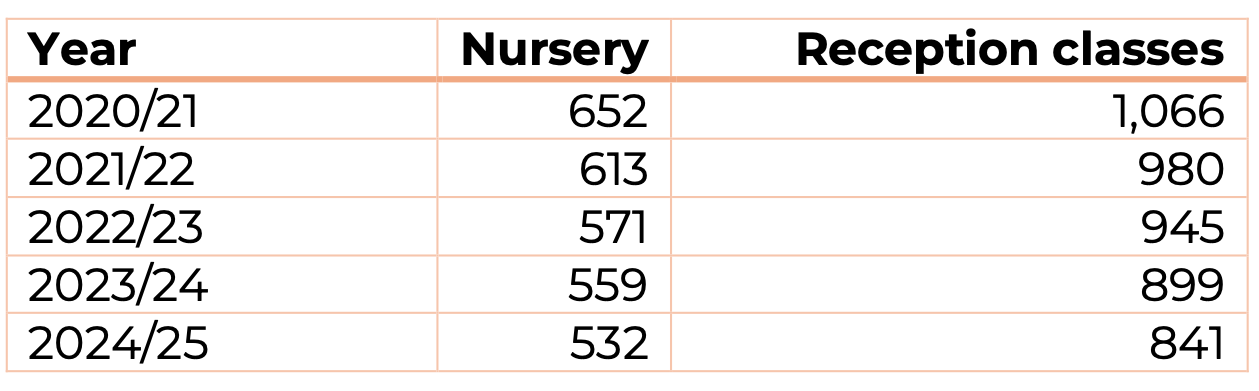

Table 2 Number of children in state nurseries and reception classes, 2021/22-2024/25

Source: Schools, pupils and their characteristics.

Note: The figures are calculated through a census conducted every spring.

The numbers will fall further given the fall in the number of births. The figures in Table 1 suggest that the number entering reception classes is likely to fall to around 730 within four years.

One possible response to these demographic changes is to repurpose primary-school spaces for younger children – a goal that the government may have originally envisaged. However, there are obstacles -

- Buildings must be adapted for younger ages; what is suitable for four-year-olds is not for three-year-olds.

- Recruitment campaigns for staff in this age group have struggled to achieve success.

Legal provisions

The relevant legislation is the Day Care of Children (Jersey) Law 2002, which provides the legal framework of requirements for registered childcare providers. Under Article 4, the Minister may impose requirements on childcare providers – currently the Early Years Statutory Requirements, which cover the period from birth to school-entry age.

In line with other policy areas, the law gives the Minister broad powers to impose requirements that have the force of law, without requiring consultation or consideration by the States Assembly. The statutory requirements are very detailed and cover safeguarding, children’s welfare, health, premises, learning and development, working together and leadership/management. They specify maximum child-to-staff ratios and required staff qualifications.

The Childcare and Early Years Service (CEYS) is part of the Children, Young People, Education and Skills (CYPES) Department and is responsible for the registering and regulating childcare providers.

Providers of childcare

Several types of provider deliver childcare services:

- Private day nurseries (Largest Category): 17 nurseries, officially described as “registered settings”, covering children from birth to school entry age; typically open 7:30am–6:00pm, year round (some term-time only). They serve over 1,000 working families.

- Pre-schools: 10 centres for children aged 2 to school entry age; term-time only; 5 are attached to private primary schools; 5 are stand-alone.

- State primary schools: 21 of the 24 schools have nursery classes for the two years before reception; these operate term-time only.

- Registered child-minders:46 individuals primarily caring for the 0-3 age range.

- Accredited nannies:27 nannies registered through the Jersey Childcare Trust’s accreditation service (nanny registration is not mandatory).

- Specialist organisations:The Jersey Childcare Trust assists children with special needs and from low-income families. It provides inclusion support, a childcare-information service, and the nanny-accreditation scheme.

- Informal arrangements:Informal arrangements also exist, some of which may fall within the categories that should be registered and regulated.

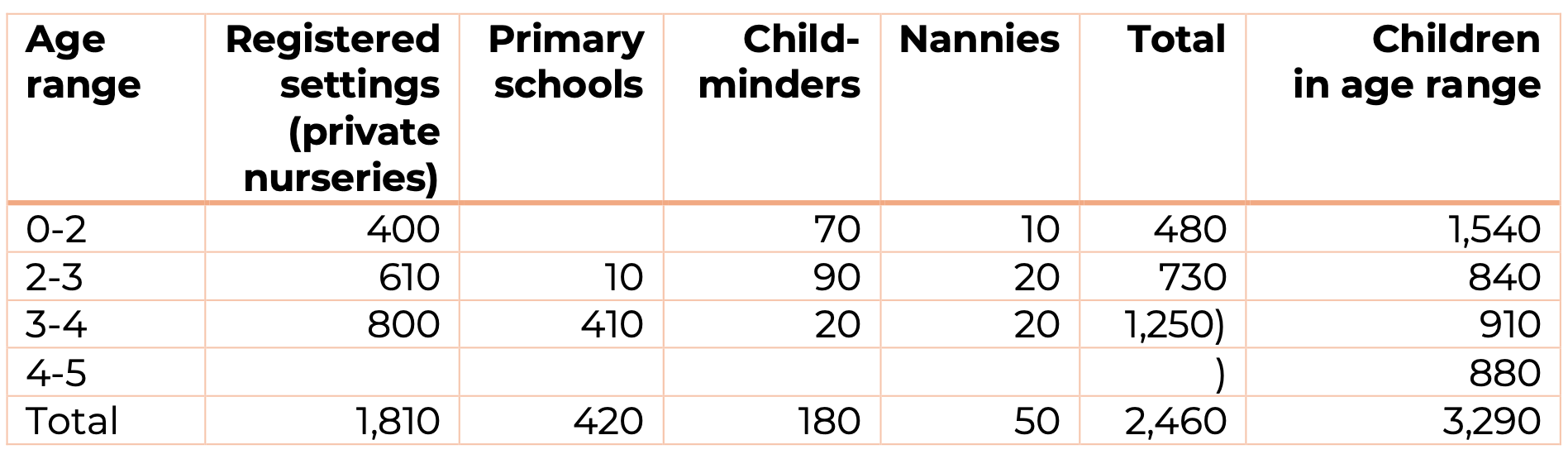

Table 3 shows estimated early years provision for the number of children in each age category in 2024.

Table 3 Early years provision, 2024

Source: 4:Insight: Early Childhood Education and Care: Jersey, 2024.

Note: The table suggests more children being looked after than there are in the 3-4 age range. This is probably largely explained by this category including some in the 4-5 age category.

The table shows that fewer than one-third of children in the 0-2 age range are in a formal early-years setting, the proportion rising significantly to 87% for the 2-3 age range. Private nurseries (“registered settings”) dominate provision across all ages; primary schools are significant only in the 3-4 age range.

By definition, no figures are available for children looked after in un-registered or informal day-care settings, which fall into several categories -

- Children cared for entirely by their parents.

- Children cared for by other family members, particularly grandparents.

- Children cared for in sharing arrangements.

- Informal child-minding where parents pay for the service.

The 2002 law defines a “day-carer” as someone who –

(a) looks after one or more children under the age of 12 years in his or her home or other place wholly or mainly used as a private dwelling for reward; or

(b) looks after any such child for a period or periods the total of which exceeds 2 hours in any day and 6 days in any calendar year.

It is an offence to be an unregistered “day-carer”. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that a number of child-minders fall into this category. Because they are not subject to the same regulatory requirements as nurseries or registered child-minders, they are cheaper than private nurseries.

Providers compete with each other and there is competition within each category. The 4Insight report highlighted the following points -

- Many providers reported that parents are choosing to have their children cared for by friends or relatives, for at least part of the week, to reduce childcare costs. This is making it difficult for providers to fill their full-time registered places.

- There is a perception of a shortage of childcare provision. However, this is not the case. Primary schools alone have 220 spare places, and as the number of children declines this surplus is likely to increase. The real issue is cost, not the number of places.

Three organisations represent childcare providers –

- The Jersey Childcare Trust: in addition to being a direct provider of specialised services and running the nanny-accreditation scheme, it also provides an inclusion-support service and a childcare-information service.

- The Jersey Early Years Association: represents all not-for-profit and private-sector day nurseries and pre-schools.

- The Jersey Association of Child Carers: represents registered child minders.

Another relevant organisation is the Best Start Partnership, whose website describes it role as follows -

The Best Start Partnership work together for babies, young children and their families to ensure that every child has the opportunity to thrive in their earliest years.

We work across traditional boundaries between government departments and partner agencies in the public, private, voluntary, and community sectors.

Together, drawing on the voices of babies, young children and their families, we drive change in early years, implement new approaches, deliver pilot programs, and develop new ways for different departments and services to work together.

It provides a wide variety of resources and services.

Costs of child care and financial support

Child care cost in Jersey are high.

- Westmount Day Nursery quotes £416 a week for children 2+, full time (50 hours a week).

- Cheeky Monkeys quotes £555 a week for the 0-2 age range, £530 for 2-3, and £448 for 3-5.

- A States Scrutiny Panel at the end of 2023 reported a fee range of £395-£517 for the 0-2 age group and £372-£476 for the 2-3 age group.

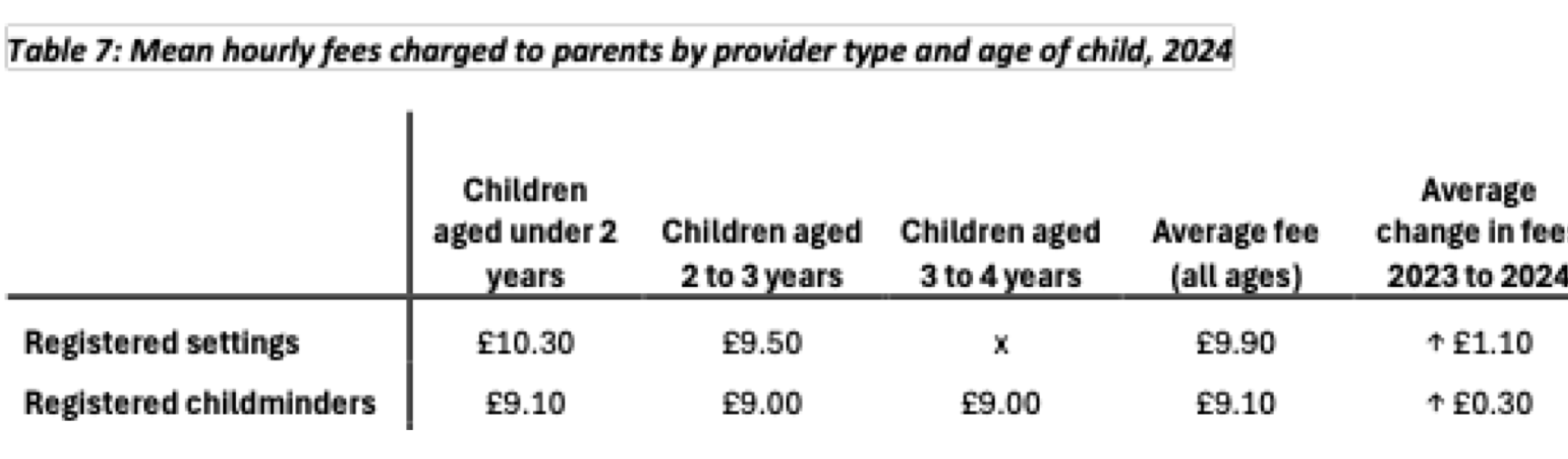

The 2024 4Insight report included the following table for hourly rates.

The report included the following on comparative costs -

Average fees charged to parents are almost 50% higher than across England as a whole and around 12% higher than in London (where fees charged for childcare are significantly higher than across the rest of the country). In Jersey, fees charged by childminders are more than a third higher than in London.

For comparison, the UK Government’s 2024 Childcare and early years provider survey recorded hourly costs in England of £6.60 for 0-2 year-olds, £6.56 for 3 year-olds and £6.36 for 4 year-olds.

Financial assistance

There are several forms of financial assistance towards meeting childcare costs.

- Tax relief: The income tax system provides for a tax free allowance of £3,950 per child (worth £1,027 a year for those at the marginal tax rate of 26%). Payments made to all registered childcare providers, government-provided nursery classes, accredited nannies and registered child-minders qualify for tax relief; families with pre-school children can claim enhanced childcare tax relief for each year of tax assessment, up to and including the year a child becomes entitled to free early-years education. The tax relief raises the tax free limit by £20,950 (worth £5,447 a year for those on the 26% marginal rate).

- Income support supplement: Jersey has exceptionally high tax thresholds, so the exemption is of little help to those on low incomes. Those entitled to income support may be eligible for a childcare component: up to £10 per hour for children under 3 and £8.37 for children 3-11.

- The Nursery Education Fund: 3-5 year-olds qualify for 30 hours of support in term time (≈ £9,000 per year). Private nurseries claim the money directly and offset it against fees paid by parents. Some charge additional fees. The funding mechanism for school-based provision is less clear.

- Support for 2-3year-olds: with effect from January 2026 parents of 2-3 year-olds can claim up to £6,270 to meet childcare costs. Unlike the provision for 3-5 year-olds parents pay for service up front and claim the cost from the Government in three instalments. Those claiming the benefit will have their entitlement to claim tax relief reduced by an equivalent amount so the net benefit for a 26% taxpayer is £4,640.

A page on the Government website Funding for early childhood education and childcare explains the various forms of financial assistance.

Government policy

The current Council of Minister’s Common Strategic Policy (CSP) lists “extend nursery and childcare provision” as a priority. It notes that children’s needs, and the demands placed on families, have become increasingly complex in Jersey, exacerbated by the high cost-of-living and limited nursery spaces. However, given the fall in the number of children there is arguably no shortage of nursery places.

Key points of the CSP:

- Any increase in provision must be matched by an increase in nursery and childcare spaces, delivered in a coordinated way.

- The aim is a universal offer for 2-3 year-olds, starting with children who have additional needs.

- Pilots will explore repurposing unused primary-school nursery space and assess availability in St Helier (the area of greatest demand) and across the island.

- The government will work with the sector to improve recruitment, retention development, and training incentives for this critical profession.

The Early Years Plan (published 30 October 2024) outlines why this CSP has been proposed.

Highlights from the “Why” section include:

- Investment primarily in increased capacity and quality of early-childhood education and care, recognising its transformative, positive effects on young children.

- Secondary benefitssuch as increased access and choice for families as nursery spaces increase, a stronger proposition for Jersey to attract and retain working families, and greater utilisation of school-workforce capacity and premises. Jersey already has high levels of participation in work, consequently, additional benefits from this investment are potentially in enabling a better balance of access to work by gender, an increase in hours of work and more choice on type of work undertaken.

- Pilots for 2024/2025 covering:

- a) Extending provision in school nurseries.

- School nurseries offering spaces for 2–3-year-old.

- A non-Government nursery operating from school premises

- A workforce support plan was stated to be “in development,” focusing on reviews, model identification and recruitment campaigns.

The “Building a coherent Early Years Policy” section states that: “in 2026 [the government will] communicate how the broader policy objective of establishing a universal offer for 2-3 year-olds can be achieved”.

How effective is childcare provision?

Early-years education serves several purposes including that children are “school-ready” when they begin primary school. Children who are not school-ready start at a disadvantage, and the higher the proportion of such children in a class, the greater the challenge for teachers.

The Children, Education and Young People Department’s Annual Performance Report lists, as a “Service Performance Indicator, “the percentage of reception children in government schools achieving the “expected level of development”. Results -

- 2023/2024: 60.9%.

- 2022/2023: 62.3%

- 2021/2022: 59.2%

- 2020/2021: 59.5%

A “green” rating requires 69.9%; anything below 61.2% is rated “red”. Three of the last four years have been “red,” with no year coming anywhere near “green”.

By contrast, by the end of key-stage 1 (age 7), the percentage of government-school pupils “assessed as reaching age-related expectations in reading, writing and mathematics” was 84.2%, above the “green” threshold of 81.5%.

Comparisons with other jurisdictions are always useful. The UK office for National Statistics provides a wide range of relevant data, broken down into local authority areas. The most comparable statistics are for “children at expected level across all early learning goals” (teacher assessments at the end of the early years foundation stage (EYFS), i.e. the summer term of reception year/ end of the academic year in which a child turns 5). In England, the proportion in 2023/24 was 66.2% (up from 65.6% in 2022/23 and 63.4% in 2021/22).

The English regions most comparable with Jersey are the more affluent areas of south-east, the figures for which are as follows.

Jersey59.4%

England 66.2%

Regions

Inner London 68.8%

Outer London 68.6%

South east 68.7%

North west 62.7%

Local authorities

Buckinghamshire 71.3%

Surrey 73.9%

Hertfordshire 69.9%

Bromley 73.2%

Richmond-upon Thames 77.1%

The methodologies used in England and Wales differ. Jersey's include a wider range of factors than England’s, which concentrates on academic performance. Also, moderation practices are different, in England nurseries can decide which curriculum to follow whereas the curriculum is Jersey is more prescribed and there is a risk of professionals concentrating on the published benchmarks. Given Jersey’s aspiration to have an educational system that is comparable with high-performing jurisdictions it would seem appropriate to seek to produce comparable data. The crude figures suggest that Jersey’s “school readiness” is significantly below the best-performing English local authorities. This seems consistent with the fact that the Jersey figure is 13% below that needed to be rated “green” under the department’s own criteria.

Policy issues

Appendix 1 summarises three recent reports commissioned by the Government of Jersey on childcare provision -

- 4insight: factual survey of providers.

- ISOS Partnership: round table discussion of providers

- ISOS Partnership: survey of parents’ and carers’ views on early childhood education and care.

Key points from the reports:

- A holistic, consolidated approach to early years provision is needed.

- Parents are mainly concerned about the high cost of childcare, with secondary worries about flexibility and lack of availability.

- Providers are mainly concerned about staffing and financial viability.

There are no simple solutions. There is no suggestion that nurseries are making unreasonable profits; rather their costs are high.

There are six challenges.

Recruitment and retention: The biggest short-term problem facing the sector is the difficulty of recruiting and retaining staff combined with increased costs that are not matched by increases in government support.

The staffing issue is particular problem in Jersey because high salaries are offered in the finance sector. This has been accentuated by a new requirement that “where staff are unqualified, they must be working towards a relevant qualification.” If they do not do so, they cannot be included in the staff-to-child ratios. Many nurseries have staff members – some with significant experience in childcare and as parents – who can no longer be counted in the ratios. It is understood that about a quarter of staff fall into this category, and those staff often have little desire to start formal professional training again. The new provision was unintended and is currently under review.

The staffing requirements are unusually prescriptive compared with many other sectors, and they therefore increase costs and reduce the size of the potential workforce.

Insufficient return-to-work benefits: Although one of the perceived advantages of early years support is to enable parents to return to work, there is little evidence that, for example, providing 15 hours of support for 2-3 year-olds will have any significant impact. Jersey already has high labour-force participation among young parents. 15 hours of support is probably not sufficient to encourage parents to return to low-paid work, while those who prefer to look after their children rather than return to work will not be encouraged to change.

Funding model stability: While expectations and costs have increased, government support has not increased commensurately. Nurseries can respond by increasing fees, but there is an understandable reluctance to do so because many parents are already struggling financially, and higher fees would reduce demand as some childcare shifts from the formal regulated sector to informal providers.

The report Early Childhood Education and Care: Jersey, 2024 (prepared for the Government by the consultancy 4Insight), said that 40% of all providers reported outgoings that threatened the sustainability of their business; continued rises in inflation and prices were the most commonly cited threat. As noted earlier, the report also commented:

Many providers reported that parents are choosing to have their children cared for by friends or relatives, for at least part of the week, to reduce childcare costs. This is making it difficult for providers to fill their full-time registered places

Public-vs-private sector provision: As demand for primary-school places has fallen, schools have increasingly competed with private nurseries for 3–4-year-olds. There is a question as to whether the competition is fair. It is understood that primary schools do not pay rent for the premises they occupy, unlike private nurseries. Funding arrangements for primary-school nursery places are opaque, but they appear to depend more on the number of classes then on the children accommodated, which can lead to very small nursery class sizes – something that is not viable for private nurseries.

Expenditure balance across age-groups: Research indicates that the maximum return on investment comes from spending on the younger age groups, yet current expenditure is biassed toward older groups. Addressing this imbalance cannot be achieved through day-to-day policy tweaks; it requires a fundamental review leading to long-term policies.

Outcomes: Jersey produces school-readiness results that seem to compare unfavourably with those in the South East of England and fall well below the government's own target. One reason for this may be that early intervention practices are more developed in England than in Jersey.

Appendix 1 Recent research

This appendix sets out summaries of three recent research reports on early years provision.

Early Childhood Education and Care: Jersey, 2024, by the consultancy 4Insight.

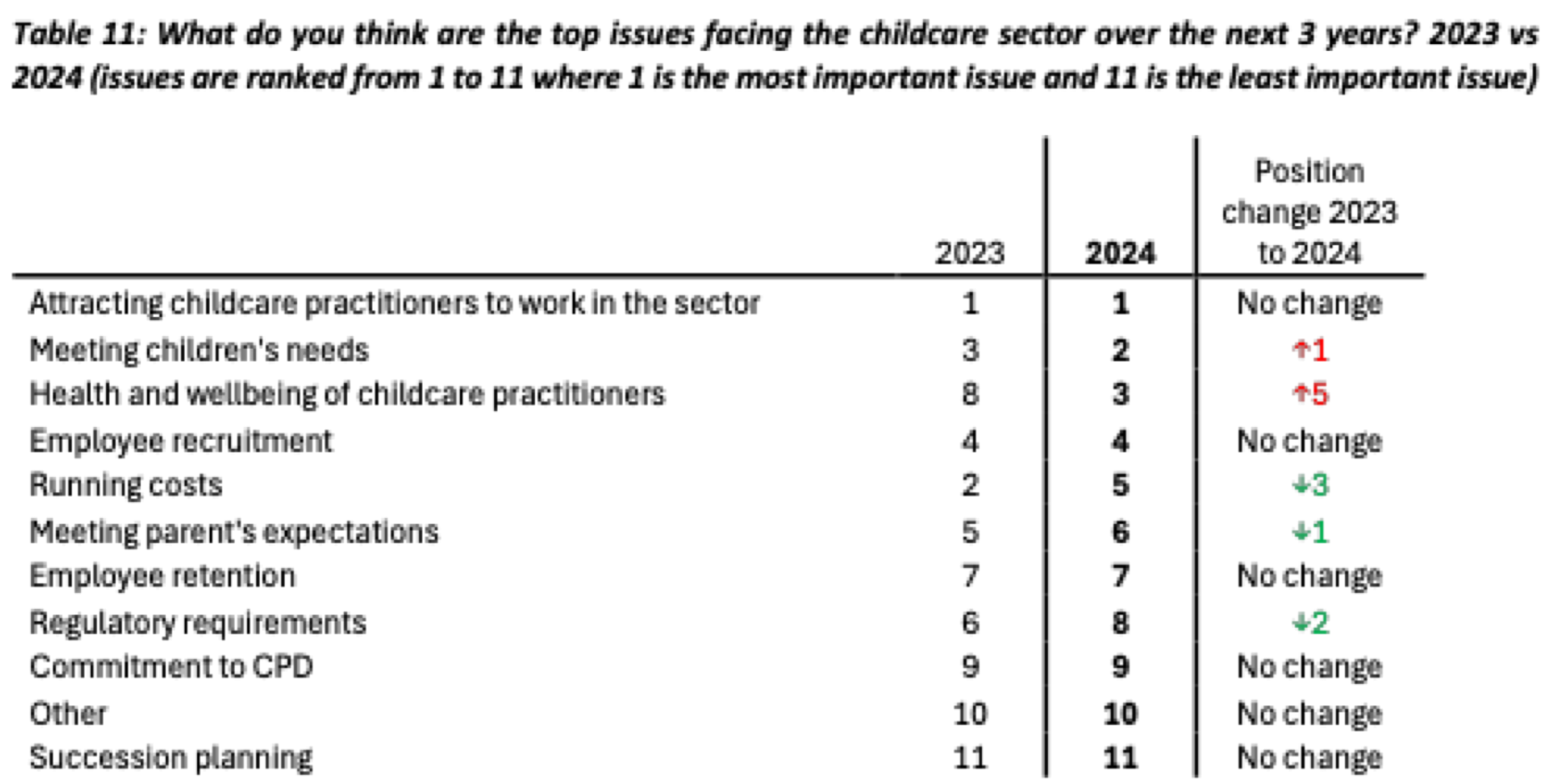

The report included the following table showing the top issues as identified by childcare providers.

On costs the report concluded -

- In Jersey, fees charged to parents are around 50% higher than in England as a whole and 12% higher than in London (where fees charged to parents are significantly higher than across the rest of the country); fees charged by childminders are 30% higher in Jersey than in London.

- The largest outgoings for registered settings are employee salaries followed by facilities (i.e.rent/mortgage payments and property maintenance) and materials; for childminders the largest outgoings are social security and ITIS payments followed by materials and petrol/parking.

- 40% of all providers said they had outgoings that were threatening the sustainability of their business; continued rises to inflation/prices was the most commonly cited issue threatening sustainability.

The report also commented –

Many providers reported that parents are choosing to have their children cared for by friends or relatives, for at least part of the week, to reduce childcare costs. This is making it difficult for providers to fill their full-time registered places

Early Years RoundTable Series 2023/24, by the consultancy ISOS Partnership.

Between November 2023 and January 2024, a group of 24 early years stakeholders met for a series of roundtable discussions, facilitated by the ISOS Partnership. The report was published in March 2024. The executive summary of the report identified five key overarching principles for policy –

- We need to be holistic and joined-up, thinking across service and setting boundaries.

- We need a clearer offer to families - but not a “one size fits all” solution.

- We need to empower parents as children’s primary caregivers and first educators.

- We need to harness and build on existing system strengths – including Best Start.

- We need to learn from past experiences and develop a sustainable model for change.

The discussion generated five policy imperatives. In summary –

- Provide accessible support from the very start, and ensure no child or family goes unseen or falls through the net.

- Improve the supply and shape of early education and childcare places to better match the needs of Jersey families by engaging and listening to parents to better understand needs and plan provision, encouraging school and private and voluntary providers to work together to address gaps in flexible provision in local communities, and by prioritising workforce challenges across the island.

- Enable all families to make positive choices about how they balance family life and work without affordability being a barrier by extending the funded free offer, starting with a free funded early childhood education and care (ECEC) for 2–3-year-old children from low income households or otherwise at risk of disadvantage, and a stronger offer for children with emerging special educational needs and disability.

- Address challenges to recruiting and retaining capable and motivated early years practitioners through an innovative modern workforce strategy which adopts new recruitment approaches to attract the most able and motivated candidates, addresses low pay and regulatory challenges faced by childminders, and draws on community expertise and strengths to build quality throughout the system.

- Continue to evolve and strengthen systems for oversight and accountability.

Parents’ and carers’ views on early childhood education and care in Jersey by the ISOS partnership for the Government of Jersey, September 2025.

The report is based on 1,250 responses to an online survey of parents and carers in Jersey, alongside four in-person focus groups, conducted in June 2025. Following is a summary of the executive summary of the report.

Parents and carers who make regular use of childcare in Jersey have two key motivations for doing so: enabling employment and supporting child development. The motivation to remain in employment is primarily, although not exclusively, financial. Although high childcare costs mean the financial returns to working are often minimal once salaries are netted for childcare, parents feel access to affordable childcare enables them to maintain a career and that continuing in employment supports their mental health.

79% of parents and carers of 0-5s responding to the survey make regular use of some form of childcare - predominantly registered childcare settings and informal childcare (family, friends and neighbours). Demand for childcare is strongest in the half-time to full-time range (21 hours or more per week), and three quarters of parents said they make use of full days of childcare.

What's working well for parents?

- The majority of parents and carers seem to be reasonably happy with the quality of childcare in Jersey.

- Parents using two of the pilot provisions visited spoke positively about the quality of the childcare provided in these settings.

- Parents also have positive views of the Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home Visiting (MECSH) programme run by Family Nursing & Home Care.

- The vast majority (93%) of survey respondents are aware of the current offer of 30 funded hours per week, for 38 weeks per year, for children in the preschool year in nursery before they start school – or Nursery Education Fund (NEF).

Barriers to access

A fifth of parents with children aged 0-5 surveyed do not make regular use of any form of childcare. While some parents and carers choose, and are able, to look after their children themselves, others want to make use of childcare but face barriers to doing so. The three key barriers parents face are affordability, availability and flexibility –

- Affordability - 95% of parents we surveyed feel the affordability of childcare in Jersey is “very poor” or “poor”.

- Availability - 79% of the parents surveyed said there are not enough childcare places in Jersey.

- Flexibility - parents and carers feel childcare providers tend to offer limited or inflexible hours, with a lack of holiday provision, early morning and evening sessions.

Access to information

The majority of parents responding to the survey feel there is too little information about childcare in Jersey.

Access to NEF entitlement

93% of survey respondents are aware of the current NEF offer, and 87% of parents and carers of children aged 4 surveyed said they make use of their funded hours through NEF. Parents and carers with NEF-eligible children identified two main barriers to accessing their funded entitlement.

- Some parents are using forms of childcare that are not covered by NEF, such as childminders, or specialist provision in PVI settings that are not NEF-registered.

- Some parents flag that they do not understand the NEF scheme and need access to better quality information.

Parents of three-year-olds born after September voice frustration at having to pay for an additional year of childcare before they are eligible for NEF.

Taken together, the research findings lead to nine key insights to guide next steps:

1. Build a stronger early years workforce

2. Expand provider capacity

3. Extend the current NEF ECEC offer

4. Address the issue of flexibility

5. Set the standard for all employers in Jersey to adopt family-friendly cultures and practices

6. Build on the strengths of existing provision

7. Put in place an urgent workforce strategy to address the acute shortage of specialist capacity

8. Strengthen mainstream providers’ expertise in supporting children with additional needs

9. Promote the Children and Families Hub as a centralised online source of reliable, regularly updated.

Appendix 2 Early years provision in England

There is a good summary of funding early years provision in a House of Commons Research Paper Early years funding in England , by David Foster, July 2025.

Since September 2025 the following free support is provided in term time –

15 hours a week for all three and four-year-olds.

30 hours a week for children aged nine months to three years .

The national average hourly funding rates are -

Three and four-year-olds: £6.12 per hour.

Two-year-olds: £8.53 per hour.

Children under two: £11.54 per hour.

A Department for Education analysis in November 2024 suggested

half of providers reported income that did not fully cover their costs.

In its 2024 report on education spending, the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank said that, while funding rates for children aged two and under in 2024/25 were “much more generous than current market rates”, funding rates for three and four-year-olds were much closer to market rates. It also estimated that core funding per hour for three and four-year-olds was 8% lower in real terms in 2024/25 than in 2016/17 once provider costs are taken into account.

£8.48 billion is allocated to early years in 2025/26, comprising -

£3.8 billion for 3-4 year olds (45%)

£2.125 for 2 year olds (25%)

£2.33 billion for under 2s (27%)

£244 million for special schemes (3%)