Policy Brief

Cost of living

Introduction

Surveys of public opinion show that the cost of living is considered to be the main issue facing Jersey today. This paper analyses the available evidence on the cost of living in Jersey, in particular how it impacts different categories of household, and discusses ways in which the cost of living can be reduced. It complements the Policy Centre’s research paper Low Income in Jersey.

Summary

- Opinion surveys show that the cost of living is regarded as the most important issue facing Jersey. This view is most strongly held by families with dependent children.

- The real issue is the relationship between income and expenditure. People’s views are influenced by the fact that average real incomes, that is earnings adjusted for inflation, have not increased since the beginning of the century.

- Housing costs, widely defined, account for around 30% of household expenditure, and food and non-alcoholic drinks 11%, with a variation from 16% for the lowest income households to 8% for the highest.

- There are huge variations in respect of housing costs. They are minimal for those owning homes outright or with a small mortgage and those whose rent is met by income support, and very high for those who have recently purchased or who are paying a market rent.

- The cost of living in Jersey is at least 10% higher than in the UK. House prices are slightly higher than in London, 51% higher than in the south east of England and 23% higher than in Guernsey.

- Groceries are 14% more expensive than in the UK, made-up of 8% distribution costs, 3% labour costs and 3% tax differences. But the absence of lower price grocery retailers mean that cheapest grocery retailers in Jersey can be up to 49% more expensive than in the UK. Hower, the competition authority has concluded that the grocery market is functioning well from a competition perspective, with a range of grocery retailers and no sign of excess profitability.

- In 2020/21 average household income before housing costs in Jersey was 51% higher than in the UK, and after housing costs 42% higher. Combined with the high threshold for income tax this means that on average living standards in Jersey are higher than in the UK.

- The headline figure for the cost of living can be reduced by shifting taxes from expenditure to income but this would have the effect of reducing post-tax income.

- .Jersey is part of the UK’s monetary union and inflation in Jersey will closely match that in the UK.

- Government policy directly increases prices in some areas including taxis and housing.

- Competition policy can play a role in reducing prices through tackling anti-competitive practices, but in practice has not done so.

- Amazon and other online retailers enable Jersey residents to obtain some goods at lower prices than are available in the local market.

- The obvious sector where the cost of living can be reduced is housing, which requires policies that increase the supply of housing. A second sector is retailing, specifically by actions to encourage low-cost retailing.

Cost of living is the main public concern

Surveys of public opinion in Jersey show that the main concern is the cost of living. The most recent survey , conducted by the Policy Centre in January 2025, showed that, unprompted, the most important issues facing Jersey were considered to be cost of living (29%), housing (17%), faith in government (9%) and population levels (9%). When asked about other issues from a list, the combined figures for most important/other issues were cost of living (64%), housing (59%), the hospital (51%), healthcare (49%) and faith in government (45%). The figures for housing reflect the high cost of housing and therefore can be considered also to refer to the cost of living.

The averages conceal significant variations. Cost of living was significantly more important for those with dependent children than for those without and for those in the 35-54 age group than for those in the other age groups.

The Jersey Opinions and Lifestyle Survey Report 2025 includes relevant data. The proportion of people who reported that they found it difficult to cope financially ranged from 69% for single parents to 44% for working age people living alone, 35% for couples with children, and 17% for pensioners.

Recent trends

Statistics Jersey publishes detailed quarterly reports on retail price trends, most recently the Jersey Retail Prices Index December 2025 report.

The rate at which prices increase in Jersey depends essentially on what happens in the UK. Jersey is part of the UK’s currency area that the factors that affect prices in the UK apply to a large extent in Jersey.

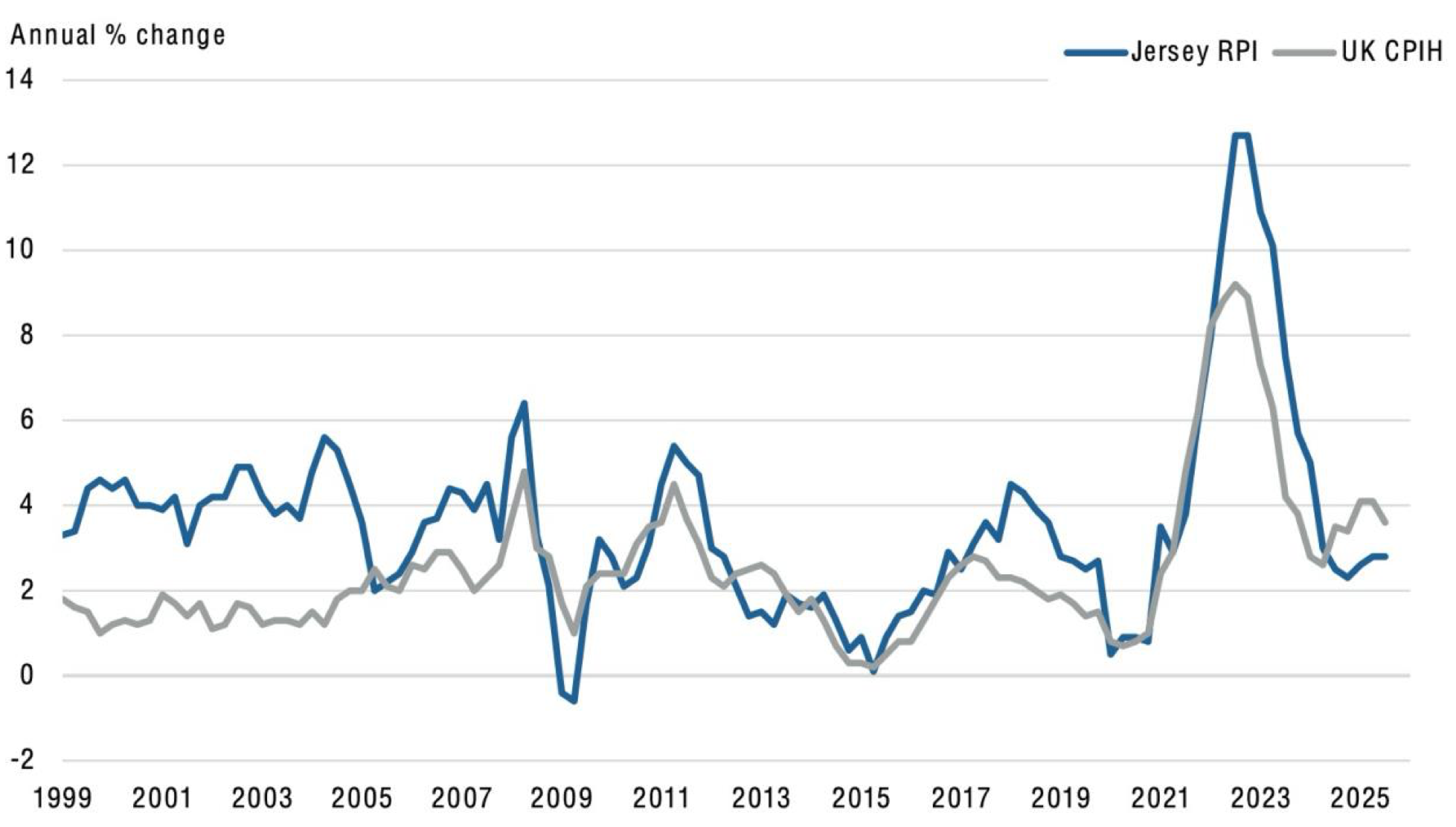

The report shows how changes in the rate of inflation in Jersey match UK trends. The following graph shows the position.

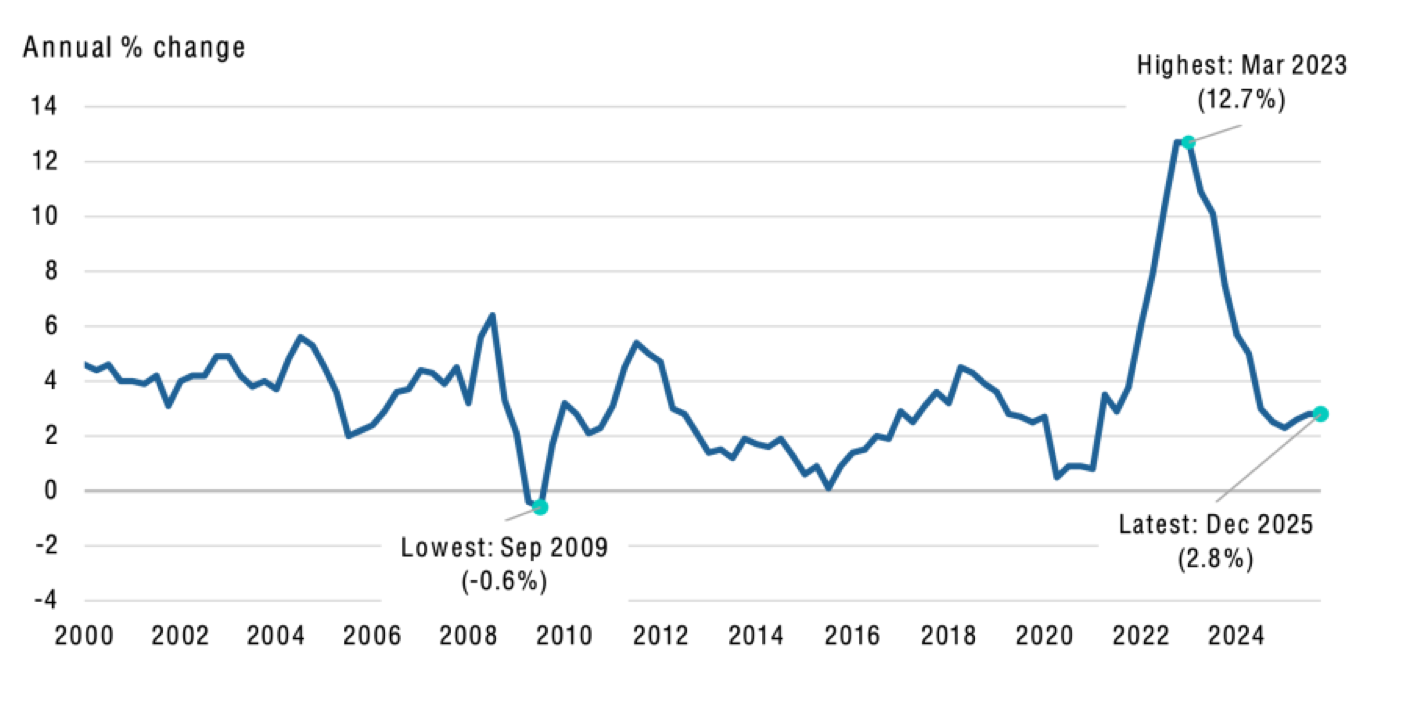

The report also shows how inflation has slowed markedly from a peak of 12.7% in March 2023 to the latest figure of 2.8%. A fall in the rate of inflation does not mean that prices are falling; rather than prices are rising more slowly. The following graph of Jersey’s RPI is reproduced from the report.

Price increases affect different groups of people in different ways. For this reason, Statistics Jersey publishes four additional measures of inflation. These can vary in the short term, but these variations tend to even out over time. All-Items Retail Prices Index (RPI) increased by 2.8% in the year to December 2025 to stand at 240.3 (June 2000 = 100). The comparable figures for the year to December 2025 were –

- RPI(Y), which measures underlying inflation, 3.8%.

- RPI(X), which excludes mortgage interest payments, 3.7%.

- RPI Pensioners, 3.9%.

- RPI Low Income, 3.6%.

Jersey’s Fiscal Policy Panel is forecasting that the underlying rate of inflation will be 3.6% in 2026 and 3.0% in 2027.

The real issue is income in relation to expenditure

While people refer to the cost of living as being a problem, the real issue is the relationship between income and expenditure. An individual would accept a 10% increase in the cost of living if they had a 50% increase in income. However, if everyone had a 50% increase in income then there would be a consequential increase in the cost of living.

It is helpful to put current views in context. Average real earnings, that is earnings adjusted for inflation, have not increased since the beginning of the century. The Statistics Jersey June 2025 report Index of Average Earnings commented that “It is apparent that in Jersey there have been three periods of change in real-term average earnings:

- 1990 to 2001 saw real-term growth in earnings of more than a sixth (18%) over the period

- 2001 to 2020 saw earnings remain essentially flat in real terms, increasing by 0.7% over the 19-year period

- 2020 to 2024 saw earnings decrease in real terms, decreasing by 3.3% over the 4-year period.”

It follows that public policy should not be narrowly focussed on the cost of living but rather on both income, widely defined to include benefits, as well as costs. Governments everywhere can reduce the cost of living by reducing taxes on expenditure, making up the shortfall by increasing taxes on income. This would have significant distributional consequences between different groups with some being better off and others worse off. The overall effect would depend on changes in behaviour, but generally tax changes can have only a limited effect on living standards for the community as a whole as opposed to particular groups.

Different types of household have to meet different costs

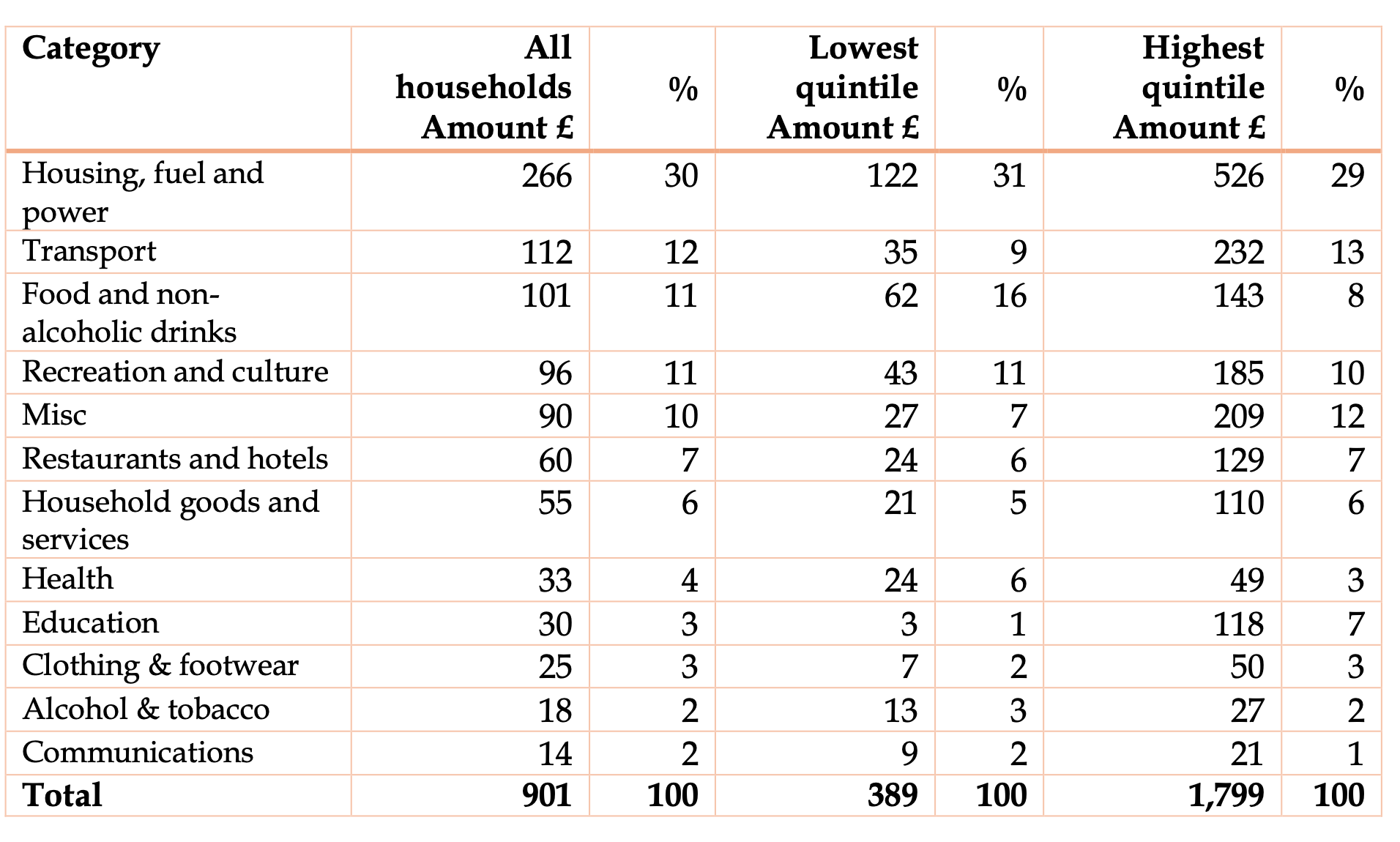

The most recent data on what households spend money on is the Statistics Jersey report Household Spending 2020/2021 . While the absolute figures will have changed significantly from then it is doubtful if the percentage breakdown has. Table 1 shows the breakdown of expenditure for all households, for households in the lowest income quintile (the 20% of households with the lowest incomes) and for those in the highest income quintile (the 20% of households with the highest incomes).

Table 1 breakdown of weekly expenditure by household 2020/2021

Source: Statistics Jersey. Household spending 2021/2022.

In general, the variations in the breakdown of spending between the lowest and the highest income quintiles are fairly small with the significant exception, not surprisingly, of food and non-alcoholic drinks. That proportion ranged from 16% for the lowest income quintile of households down to 8% for the highest. However, those in the highest quintile spent an average of £143 a week on food and non-alcoholic drinks while those in the lowest quintile spent £62.

Housing is a key issue

The housing figures need unpicking for two reasons. First, housing is a major component of household expenditure, particularly so as housing costs are exceptionally high in Jersey.

Secondly, the figures are not quite what they seem because the rent figures take no account of income support. So, for example, a tenant qualifying to have all their housing costs met by income support is recorded as paying the full rent and at the same time receiving income equal to the rent.

Table 2 sets out the key figures from the Household Spending report for the different housing sectors.

Table 2 Weekly expenditure on housing 2021/2022 by tenure

The housing category is broken down into rents (39%), mortgage payments (37%), energy (13%), maintenance and repairs (3%), rates (3%), water (3%) and sewerage (3%). Energy costs explain most of the expenditure by those owning outright.

On the face of it those owning outright are in a different position from every other category with just 10% of their income going on housing costs, widely defined, while for the other categories the proportion is between 34% and 39%. But, in practice, many tenants receive income support to meet their housing costs ranging from all housing costs in the case of some Andium tenants to a significant proportion for almost all other Andium tenants and many other social and private sector tenants.

Households in two categories face particularly high housing costs: those who have bought in the last few years when house prices were at their peak and also having to face in many cases significant increases in mortgage rates, and tenants in the qualified and non-qualified rental sectors who are paying a full market rent but who whose incomes are such that they are not entitled to income support.

Comparison with the UK

There is no recent comparison between Jersey and UK prices. In 2013, a one-off exercise was conducted by Statistics Jersey Jersey - UK relative Consumer Price levels for Goods and Services 2013. The summary of the report is set out below –

- Price levels for consumer goods and services (excluding housing costs, health and education) in Jersey were 9% greater than the UK average.

- Consumer prices levels were marginally greater in Jersey than in London (by 2%).

- Price levels for food and non-alcoholic drinks were nearly a fifth greater (19%) in Jersey than the UK average.

- There was large price variation for the expenditure categories comprising predominantly services; household and housing services were nearly a fifth greater in Jersey (19%) than the UK average and miscellaneous goods and services were 15% greater in Jersey.

- There was little variation in price levels for alcohol (off-license sales) and tobacco. Price levels in Jersey and the various UK regions were similar to the UK average.

- Price levels for clothing and footwear were 8% lower in Jersey than the UK average.

- The overall price level for consumer goods and services in Jersey (when housing costs, health and education are included) was a fifth (20%) greater than the UK average.

Table 3 shows the key data.

Table 3 Percentage difference in price levels between Jersey and the UK, 2013

This was an extensive exercise, and it has not yet been possible to repeat the study.

Although prices in Jersey are higher than in the UK so are incomes. The Jersey Household Income Distribution 2021/22 report showed that median equivalised household income before housing costs was £860 in Jersey, 51% higher than the UK figure of £565. After housing costs, the differential was 42%. This factor, combined with the high threshold for income tax, means that on average living standards in Jersey are higher than in the UK. It is also the case that the higher incomes are themselves a significant contributor to prices being higher as labour costs feed through to consumer prices.

It is useful to look at the data for the two important sectors – housing and groceries.

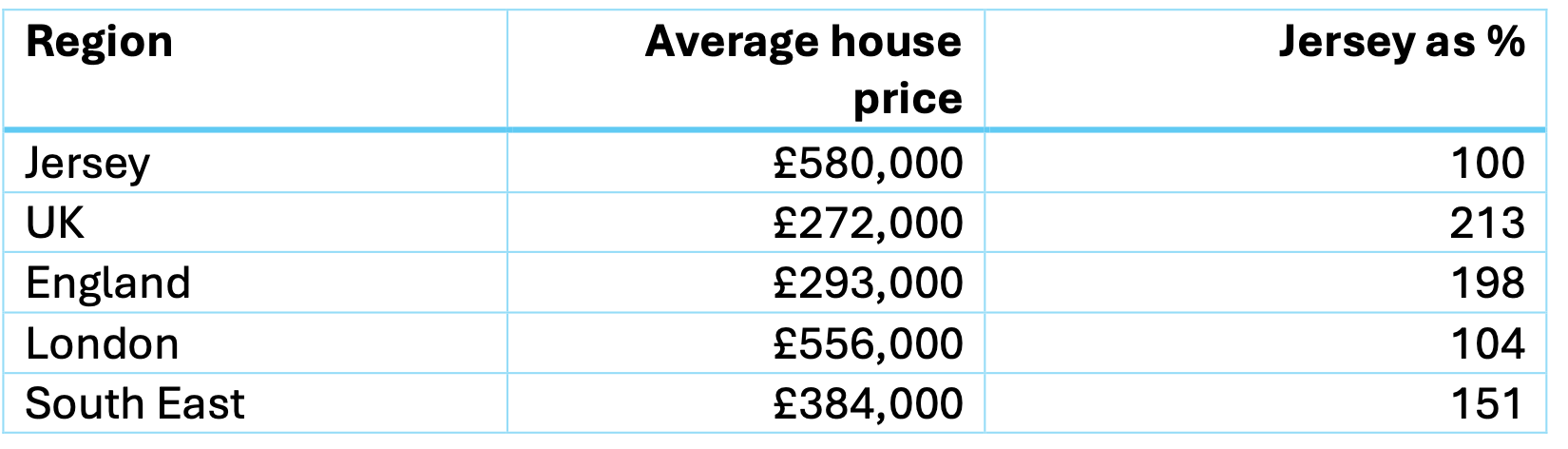

The high cost of housing in Jersey can be illustrated by comparison of house prices with other jurisdictions. Table 4 shows the data.

Table 4 Mix-adjusted average house prices, Jersey and UK, Q3 2025

Source: Statistics Jersey. Housing Affordability webpage.

It will be seen that house prices on average are slightly higher than in London and are 51% higher than in the rest of the south east of England. Statistics Jersey calculates that, on a comparable basis, in 2025 Q3 house prices in Jersey were 23% higher than in Guernsey.

In addition to house prices being higher in Jersey than in the UK, mortgage rates are also higher, currently by about 0.6 percentage points, or 15%. This means for example that on a £400,000 mortgage a borrower in Jersey is paying £2,400 a year more in interest than a comparable borrower in the UK. The reasons generally given for this are that the banks in Jersey are not part of the UK retail banks and have higher operational costs and possibly also higher funding costs.

Rents are a function of house prices and accordingly high house prices in Jersey are reflected in high rents.

In Jersey, groceries are significantly more expensive that in the UK. In September 2023 the Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority (JCRA) published a report by the consultants Frontier Economics Groceries Market Study. This concluded that the cost of a shopping basket at the same retailer was about 12% lower in the UK than in Jersey. This 12% was made-up of 7% distribution costs, 2% labour costs and 2% tax differences. However, it added that “Jersey lacks the lower price grocery retailers – notably the ‘Big Four’ and the Discounters” and that as a result “the cheapest grocery retailers in the UK can be up to c.33% cheaper than retailers in Jersey.” It noted that “the lack of lower price retailers and higher operating costs could have a disproportionate effect on some lower-income consumers”.

This position does not result from “profiteering” but rather from the small size of the Jersey market, higher freight and labour costs and tax differences. The accompanying Groceries Market Study Findings and Recommendations by the JCRA concluded that: “The Jersey grocery market is functioning well from a competition perspective, with a range of grocery retailers and no sign of excess profitability” and that “Profits for grocery retailers are in line with expectations and benchmarks”.

However, the fact remains that Jersey’s special circumstances mean that those who shop at, for example, Waitrose or M&S are paying 14% more for their food than they would in the UK. Low income families could be paying as much as 49% more than their UK counterparts because they do not have access to a Lidl, Aldi, Costco or street markets. Low income families are therefore disproportionately impacted by grocery prices in the Island.

However, as the JCRA report noted “if a low-cost grocery retailer from the UK did enter the Jersey market, it would face the same additional costs as existing retailers“, so it would be more expensive than in the UK.

Policy principles

The point has been made that the real issue is not so much the cost of living but rather people's ability to meet the cost of living. If the policy intention is simply to reduce the headline figure for the cost of living this can be done by reducing GST and the duties on petrol, alcohol and tobacco, and increasing income tax. In fact, for three years the Jersey Government chose to freeze the duty on petrol on cost of living grounds, at the expense of another policy of reducing carbon emissions.

The effect of such measures on average would be minimal as people would be paying the same amount of tax in a different way and their standard of living would be unaffected. However, depending on how the tax increases were structured there could be significant distributional effects and also effects on behaviour. Increases in income tax are capable of reducing the tax yield if the effect is to cause people to work less or to leave the Island.

These issues and the wider policy issue of tackling the problem of low income are considered in detail in the Centre’s research paper Low income in Jersey. They requires a holistic approach covering the full range of taxes and income support. In general, the most efficient way to help those on low incomes is not through seeking to reduce the cost of those items which they are most likely to buy but rather by increasing their income through the benefit system. This is the policy followed in Jersey and in most other jurisdictions.

However, it is important to consider whether actions can be taken which will have the effect of reducing the cost of living without requiring compensating increases in taxation, thereby increasing real incomes across the board or for some categories of household. The policy options are limited. Jersey is part of the UK’s monetary union and the reality is that inflation in Jersey will closely match that in the UK and there is very little that the government can do about it.

However there are some measures that could properly be considered, which mainly involve tackling high costs caused by the government itself.

High prices caused by Government

Until recently licensed premises were subject to “guidance” issued by the Attorney General which in practice banned –

- Any promotion that results in one or more alcoholic drinks being offered for sale at a price below the relevant stated price on the displayed tariff, for example buy one get one free, lower prices at certain times of the day or week and loyalty card schemes.

- Charging prices more than 10% below that charged in other premises.

These were very unusual requirements, effectively preventing licensed premises from offering lower prices. In 2021, the Attorney General asked the JCRA to review the guidance. Its report concluded that -

- Jersey’s on-licence pricing restrictions are unique. Stakeholder feedback, economic theory and market outcomes all suggest they restrict competition.

- High prices in the on-licence sector are likely to lead to a shift away from on-licence to off-licence consumption. This is a trend identified by stakeholders and is consistent with economic theory, and the weight of econometric evidence from other countries.

- There are relatively higher on-licence prices on Jersey. This suggests the removal of pricing restrictions and responsible use of promotions could encourage competition and benefit consumers.

Notwithstanding the obvious consequences of the guidance and the conclusions of the JCRA study it was May 2025 before the guidance was withdrawn. This resulted in some licensed premises immediately offering promotions, that is lower prices.

There is currently another area where government policy results in prices being exceptionally high, that is licensed taxis. A person who is qualified to be a taxi driver cannot obtain a vehicle licence unless they meet four restrictive conditions –

- Taxi driving must be the main employment/income and with a minimum mileage of 19,100 miles.

- Be affiliated to a specified company/booking entity and can change only with the permission of DVS (the government agency).

- Spend 18 months as a driver for a recognised company.

- Purchase a vehicle than meets minimum requirements in respect of type, age and mileage.

These are significant barriers to entry, which presumably is the intention. The result is very high taxi fares. A JCRA study in 2010 commented –

The cost of a rank taxi cab journey in Jersey is among the most expensive in the United Kingdom (“UK”). A two-mile daytime journey cost 7% more in Jersey compared to the average price in the South West of England and almost 20% more compared to the UK national average. For a five-mile daytime journey in Jersey the situation improves as the cost is just under the average cost in the South-West of England, but it is still 13% more than the UK national average. These comparisons are with the VAT and GST included in the fares.

The Policy Centre undertook a limited study for its 2026 paper Regulation of taxis. It noted that fares were typically 25% - 40% higher than in comparable jurisdictions in the south east of England. A specific comparison was done with the borough of Lewes as typical of the south east. A ten-mile journey on weekdays would cost £33.95 in Jersey compared with £23.90 in Lewes. On Sunday, the comparison would be £48.05 compared to £25.50.

There is a demand in Jersey as elsewhere for a low-cost taxi service, people accepting that low cost means a more modest vehicle. There is also a potential supply of people willing to work part time as a taxi driver as they do in most jurisdictions. But the regulations effectively prevent such a service being provided, which explains the high taxi fares. This is partly mitigated for some people using an informal taxi service, but many people are uncomfortable with using an unregulated service. However, as with groceries if the regulations were changed to permit a low-cost tax service the higher costs of operating in Jersey would mean that prices would be higher than for comparable services in the UK.

Policy on housing

Businesses complain about a number of government policies which have the effect of increasing their costs and which therefore have an effect, albeit quite small, on the cost of living. Planning policy is the obvious example, not just the delay and cost of making planning applications but also requirements of the planning system. For example, developers have been required to provide parking spaces even where the demand for them is limited such as in the town centre. Requiring an apartment in St Helier to have a parking space adds about £50,000 to the cost or the equivalent of £2,500 a year. Similarly, the government has recently increased the minimum size of apartments which inevitably increases the cost of those apartments. This denies people the choice of paying less for smaller apartments.

More generally, the very high cost of housing in Jersey is caused by increases in demand not being matched by increases in supply. The planning system has a number of built-in features which restrict the supply of housing. In its Housing market review in 2024, Jerseys Fiscal Policy Panel commented –

- Environmental restrictions in Jersey present hard limits to development.

- Development is restricted outside of the built-up area, which covers 12% of the Island. These restrictions are justified by conservation but represent a constraint on the amount of new housing supply that can be generated.

- The planning system can also create barriers to new housing supply.

- Features of the system, such as third-party appeals and delays in reaching decisions on major applications, create uncertainty over outcomes and act as barriers to bringing new supply forward.

In addition to these points, even when a planning application is fully in accordance with agreed policies politicians sometimes decide to reject applications. This was done for the planned Les Sablons development in St Helier. The Minister was found to have acted unlawfully in rejecting the application but the damage was done because of the delay that had been caused and the site is currently derelict. Also, the Planning Committee has on a number of occasions turned down applications for housing developments even though they were recommended for approval by officers as complying with policies.

The high cost of housing in Jersey is a direct consequence of political decisions which have restricted supply.

Competition policy

Jersey is a small market so that in many sectors there are only a few suppliers. It follows that there is scope for suppliers with a large share of the market to abuse their dominant positions. As in other jurisdictions Jersey has a competition law and a competition authority, the JCRA, to tackle the problem of uncompetitive practices. The JCRA has power to investigate perceived abuses of a dominant position and to take the appropriate action. However, the JCRA is a small regulator with limited resources, and organisations which have a dominant position tend to be large and quite willing to fight any regulatory measures with an unlimited budget. In practice, the JCRA seems not to have identified areas where there has been abuse of market power or anti-competitive practices and where it has required remedial action to be taken.

The JCRA also has power to undertake more general market studies and to make recommendations. However, it must question whether there is any point in doing so if its conclusions are ignored. The JCRA’s conclusions on alcohol licensing in 2021 were ignored until 2025. The JCRA report on taxis in 2010 has similarly been ignored.

It is doubtful if there are competition policy issues in Jersey which have a significant effect on the cost of living. However, the specific examples of alcohol licencing and taxis have been given, and there is scope for it to make a modest contribution.

The Amazon effect

A significant phenomenon in the retail sector over the last few years has been the growth of the online market, led by Amazon. This has increased the choice Jersey consumers have and also their ability to buy at lower prices than are available on the Island. Indeed, when people buy from Amazon they pay less than the advertised UK price as purchases are subject to GST which is at a lower rate than the UK VAT. However, online purchasing is largely restricted to physical goods and in practice does not include groceries. It follows that only a small proportion of consumer expenditure can benefit from online shopping and therefore the overall effect on the cost of living is quite small.

Conclusions

The cost of living in Jersey is high, largely because of high housing costs but also because Jersey is a small island market. There is little that can be done about the small island market issue.

The obvious area where the cost of living can be reduced is housing, which requires an understanding that the price of housing reflects the balance between supply and demand and, following on from this, policies that increase the supply of housing.

The other area, particularly relevant for lower income households, is whether there is scope for a low-cost retailer in the Island. The issue is not so much the size of the market and whether a suitable site can be found but rather whether the additional costs of operating in Jersey could justify the investment.